Brief Interviews with Ingenious Men

Pulitzer-winning playwright Donald Margulies makes his big screen debut with The End of the Tour, a look at brilliant and tragic writer David Foster Wallace at the height of his rock star-like success.

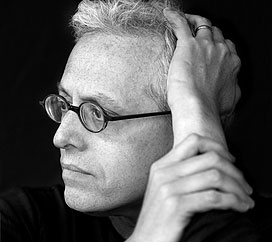

Donald Margulies

Donald Margulies

A lot of people who see the movie have assumed that I’m a first-time screenwriter because my career has been pretty much about writing plays, but I’ve actually written 26 unproduced screenplays!

In 1996, David Foster Wallace embarked upon a 10-city tour in support of his second novel, Infinite Jest, a mammoth, postmodern opus about near-future dystopianism, tennis, addiction and recovery, consumerism, film theory, terrorism, the act and art of reading and, quite probably, Wallace himself. The 1,100-page novel was christened as a Great American Novel – maybe the Great American Novel – its hardback edition weighing the same as a human brain or a can of Crisco shortening, making Wallace a very reluctant literary superstar. Of interviews and book signings, Wallace once said, “What a ghastly enterprise…I’m an exhibitionist who wants to hide, but is unsuccessful at hiding.”

Rolling Stone journalist David Lipsky joined Wallace for five days of the promotional jaunt, cruising through the wintry Midwest, sharing mix tapes, personal anecdotes, fear, loathing, cultural theories, and more. The joyride was intended to become a Wallace profile in the magazine, but never saw print until Wallace took his own life in September 2008 at the age of 46. Lipsky reviewed some 100 hours of taped conversations, transforming the transcripts into the critically acclaimed 2010 memoir, Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace.

Though 60-year-old playwright Donald Margulies was not “a Wallace fanboy” and his only other screen credits were adaptations of his plays, Collected Stories for PBS and the Pulitzer Prize-winning Dinner with Friends for HBO, Margulies’ virtuosity at penning intimate, resonant, tonally multifarious two-handers made him the ideal scribe to translate Lipsky’s tome for the big screen. The resulting film is The End of the Tour, starring Jason Segel as Wallace, Jesse Eisenberg as Lipsky, and directed by James Ponsoldt (The Spectacular Now), a former student of Margulies’ at Yale. The quick-thinking, soft-spoken Margulies is keen to share the experience of writing Tour, calling a journalist from the parking lot of his New Haven gym where he has been, he says, “just kicking it” before making the call. He claims he’s not jesting, infinitely or otherwise.

The author David Foster Wallace was widely considered “one of the most influential and innovative writers of the last 20 years,” as the Los Angeles Times published, and very often one of the great American novelists of the 20th century, according to publications like Time. Were you a fan before penning the screenplay for End of the Tour?

I have to confess that I was not a fanboy. Many years ago, I read his essays. I did not succeed in reading all of Infinite Jest many years ago. I was certainly aware of him and I was aware of his untimely death. He had this meteoric kind of rock star entrance onto the literary scene, but until I read David Lipsky's book, I didn’t fully understand the magnitude of his genius and what a loss his death was to our culture. In a sense, I was an imperfect reader of Lipsky’s book, but that lack of overriding familiarity or affinity allowed me to pursue adapting the book as a story of two writers, not those two writers specifically. Moreover, I saw it as David Lipsky's story of encountering someone who was not that much older than he was and who had achieved everything that he would ever hope to achieve as a writer. I just thought there was something very compelling in that dynamic.

There’s very little fawning over these characters. They’re presented, instead, as human beings, grappling in occasionally ugly ways with the same existential, ethical, and moral questions we all do – plus some fairly intense concerns about pro tennis, the Die Hard films, and Alanis Morissette.

I approached the material as a dramatist. I waited to take this treasure trove of material that was the book – almost a transcript, albeit edited of course, of a five-day road trip wherein Lipsky and Wallace talked about, well, kind of everything – and carve out some kind of narrative where there had been none. I wanted to really mine the subtext of these conversations for real content, real rhythm. I hope the audience feels this sort of subversive tug as they follow along on this road trip.

The American landscapes in the film, especially the frigid, stark, almost bereft Midwestern terrain, are kind of a perfect metaphor for the process of writing, yes?

Well, I definitely wanted that flat, wintry, Midwestern landscape as a character in the story, though I’m not sure I could – or would want to – agree with that idea. You could very well be right, though. I simply became very committed to the cinematic possibilities of that topography, that weather, those visuals. They were able to capture such incredible beauty in this film.

Proving yet again William Goldman’s old saw about nobody knowing anything in Hollywood, many people – even within the entertainment industry – have figured End of the Tour is your screenwriting debut at the age of 60.

It’s been funny, a lot of people who see the movie have assumed that I’m a first-time screenwriter because my career has been pretty much about writing plays, but I’ve actually written 26 unproduced screenplays! I’ve had this stealth career as a writer of screenplays that do not get produced! For me, End of the Tour was just a sublime experience. It was a meeting of so many aspects of my creative and personal life – from my friend and manager David Kanter giving me Lipsky’s book to James Ponsoldt being a former student of mine at Yale – and the themes of dealing with success in one’s chosen field and the conundrums that can bring, these are all things I have considered in my own life.

Fifteen years ago, you won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. For many writers, that kind of success and validation can be an enormous blessing that kicks open tightly locked doors, while for others it can be terribly paralyzing. What was it like for you in the aftermath of Dinner with Friends’ rapturous reception?

Well, you really did nail down the two options that occur with success – galvanization or paralysis. I was not fresh out of the gate when the Pulitzer happened; I was already 45-years-old. That was probably a good thing, but I’d also already been through the Pulitzer process a bit, having been a finalist in 1992 for my play, Sight Unseen…I had, up until that point, never considered prizes. I had honestly never thought about them – and then suddenly I saw a key. I could win one of these! Being a finalist kind of put me on the radar and was a very valuable piece of validation for me, personally, a boost of confidence and probably commercial validity I needed – and my career needed – in my 30s. It propelled me to the next phase of my career. By the time Dinner with Friends hit, I was fairly well equipped to deal with the ramifications. Sometimes, when people are hit with that kind of spotlight in their 20s or 30s, they’re just deer in the headlights. It can be overwhelming.

Wallace himself might have had that experience.

Yes, that’s true. He was so conflicted about all of that.

Let’s discuss the actual craftsmanship of taking David Lipsky’s book – for all intents and purposes, 350-pages of dialogue – and adapting it for the cinema.

For me, adaptation is very much akin to collage where you're given found material and you have to start from there. Maybe that’s because of my own background as a visual artist. In the case of Lipsky’s book, I was given this incredibly rich, sort of amorphous, conversation in the book, but it required my capturing and deconstructing it, creating new juxtapositions, finding a narrative form and structure. In going through that part of the process, I spent hours talking to David Lipsky, who was incredibly generous in sharing things that did not make it into his book, but allowed me to forge a deeper, more palpable connection between these two characters in the film. It was a balance of honoring his book, but also needing to reinvent it, which again, is akin to doing collage.

When I did a lot of collage as a visual artist, the process was very much the same. In deconstructing Lipsky’s book, I was able to isolate certain recurring images and themes, and I was able to bring into focus some of the more discursive aspects, some of the “inside baseball” talk between two writers, to bring it all into a clearer focus for audiences who may know nothing about being a writer or about David Foster Wallace. I have been really shocked at the numbers of people that I've encountered who have confessed that they have never heard of David Foster Wallace. That is a tremendous surprise to me. I assume that he's just part of the oxygen. If our film succeeds in awakening a new generation of readers to his genius, we’ve done all right.

That said, Wallace’s literary estate is reportedly unhappy that the film was made. What can you say about that?

I can’t really say anything about that, actually. I’m bound to not talk about it. All I can say is: we approached this with a real compassion and integrity. I think that all of us who made this movie are artists deeply committed to making a work of art about two men who cared very, very profoundly about art. If what we did can bring Wallace back into the conversation and can get people to go online and order his books and be introduced to him for the first time or return to him and appreciate what was lost, all for the good.

With the casting of Jason Segel as Wallace, it’s conceivable some film-going audiences will show up expecting some How I Met Your Mother or Forgetting Sarah Marshall shenanigans.

That's right. I know. When we first announced that we were making this movie and that Jason was playing DFW there was a chorus of groans and disapproval out there. I always sensed there was a tremendous synergy between actor and role, though, and I credit James’ instincts as the film’s director. He was absolutely right about Jason from the get-go. If audiences show up expecting whatever a “typical” Jason Segel or Jesse Eisenberg movie might be, and I don’t even know what that movie would be, there is a good possibility they will have a very engaging, enlightening experience at the movies. On the other hand, some of them may feel they were cheated of a brand of “bro-mance” to which they’ve grown accustomed. I don’t really know.

Let’s talk about the casting for a moment. In the theater world, the script is sacrosanct, while in film, no one is shy about referring to the screenplay as a “blueprint.” With big stars involved, “blueprint” can often devolve into “rough suggestion.” What was your experience with End of the Tour?

My experience with this film has been unusual. It is not typical. The actors, my director, everyone involved, they have been incredibly respectful of what was on the page. I mean incredibly respectful, as I was incredibly respectful of the material given to me to write the film.

When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer? Second to that, very few Americans these days grow up wanting to be a playwright. Tell me about that decision.

I grew up in the '60s. I grew up in Brooklyn. My parents were not intellectuals. They didn’t go to college. My father set wallpaper. My mother read a bit. They were middle class Jews in New York and one of the things they enjoyed doing was going to the city and seeing Broadway shows. They would take my brother and I often. The first play I ever saw was Herb Gardner's A Thousand Clowns. It was probably 1962 or 1963. I was a little boy, about nine-years-old, but it's a privilege to be in a Broadway theater. It felt like church. It was such a glorious, exciting experience to be inside that theater. I felt so very sophisticated, and I was very smitten. Though I was very excited by the theater, I was fairly adept at drawing as a child, which determined the course of my education. When you are an otherwise very myopic, un-athletic kid, you need something, and for me at that age, it was drawing.

When did you start writing?

By my teen years, my friends and I were writing parodies of musicals as part of our term projects or reports in our academic classes. They were just these silly things, but we had so much fun. I remember we had to do a report on the Congo, and my friends and I wrote My Fair Native – an historical look at the region, but with melodies taken from My Fair Lady. That kind of thing. I didn’t take any of it seriously, but we had fun.

Simultaneously, my artwork was getting a bit of attention, earned me a scholarship to Pratt Institute, so I began college studying art. But when I was at Pratt, I realized how much I missed the reading and the writing of other schools. Eventually, I transferred from Pratt to SUNY Purchase, where I was able to enjoy a mentor-mentee relationship with a professor there, the theater critic Julius Novick. He taught dramatic literature; there was no playwriting class at Purchase then. I credit Novick with being the man who gave me permission to write plays. At Purchase, I saw my first play produced, which was the proverbial “life-changing” moment.

In what ways did Novick give you permission?

He was just so un-withholding in his perception and appreciation of my talent, which is something every writer really needs. When he was asked on a student evaluation form if I should continue in the field of playwriting, he was unequivocal in his response. He wrote, “Yes!!!” With three exclamation points! That had a tremendous impact on me. It’s something I’ve thought about often as a teacher myself: when you identify promise in a student, don’t ever keep it to yourself. Make sure your student knows that you recognize something in him that he may not yet understand about himself. It’s a generosity that people who go into creative fields do not often encounter.

What’s the best piece of advice you can offer up-and-coming writers after so many years at the typewriter yourself?

I very often advise people not to devote all of their energies to a single project for a period of years. If you’ve been working on something for two years and you’re still not finished with it, it’s probably time to put it aside and get to work on something else. If it’s flawed after two years, those flaws will still be there when you come back to it. In the meantime, go out and write something else and learn from the flaws in that. That’s the best way to learn craft, really; it’s not about tinkering with the same piece for a hundred years. It’s about writing. Also, practically speaking, if you’ve written something promising, someone of some power or import is going to inevitably ask what else you’ve got. You’d better have something else. You don’t want to miss that opportunity.