A Moonlight Sonata

Barry Jenkins on why Moonlight has struck a deep emotional chord with audiences and what it means to write with “active empathy.”

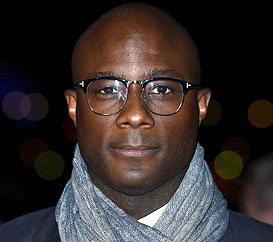

Barry Jenkins

Barry Jenkins

All I can do—all any filmmaker can do—is try to get the characters right, get the story right, be truthful to this, be truthful to that, lend it your voice and your power and your light, and then whatever you do next…Hope. Pray.

Barry Jenkins is “particular,” he says, about his coffee. It’s one of the few luxuries he has afforded himself during the yearlong whirlwind that is Moonlight.

Barely one year ago, the 36-year old Jenkins was finally calling “action” on his second feature film, nearly a decade after Medicine for Melancholy ignited feverish indie buzz, changing everything in the filmmaker’s world, but only for an instant. After the hosannas for Medicine settled, Jenkins found that he was still a kid from Miami’s Liberty Square projects, the product of a harrowing, hardscrabble upbringing trying to be more and do better, and finally, with an outlet for a voice simmering with passion and urgency. He wrote two screenplays during this time, the phantasmagorical Stevie Wonder Time Traveler and a James Baldwin adaptation, If Beale Street Could Talk, made a series of memorable television commercials, networked within the independent film community, and no matter where he looked, how hard he searched, could not find the story that would become his second feature.

Until he was introduced to Tarell McCarney’s play, In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue, which had the powderkeg effect of blasting Jenkins wide open. Turns out, McCarney and Jenkins grew up in the same neighborhood, both enduring childhood trauma, suffering through parental addictions and abuse, somehow tumbling into a brand new world. Though the paths they’ve charted and the lives they’ve led are separate, Jenkins and McCarney remarkably remain birds of a feather. In McCarney’s piece, Jenkins found his next film.

Having already lost years to the quest, Jenkins was eager to move swiftly, and so he did. Nine months after the film began production, the scorching, meditative Moonlight played to rapturous audiences at Telluride Film Festival. Since then, Jenkins has been, essentially, dancing in the moonlight, road showing the film at a half-dozen festivals, banging the drum on the film’s slow rollout, enjoying the film’s ecstatic notices and robust box office.

So give Jenkins his coffee however he wants it. Let him be “particular.” Here is an auteur in full bloom, an artist becoming, a filmmaker using his voice to find his voice and to find ours, too.

It’s been eight years between films, which is something of an eternity in today’s world, but it seems that you and Moonlight were actually right on time.

It was a long time between films, for sure. Definitely. But it’s about choices and passion, and sometimes it takes a little bit of time to get everything in alignment. Nobody wants to make a second film quickly just to make a second film. I know I didn’t. So it took some time of being in the world and actually living a life and doing different jobs and stuff to find what the story I had to tell and then make it happen.

The story you finally chose, Moonlight, is urgent, but hushed, brutal but breathtakingly beautiful, almost eerily autobiographical, and yet based on a piece by another writer.

Yeah, basically, it took a lot of years for me to just go around the block a couple of times. I read Tarrell’s piece and I saw myself in it. Despite the differences between myself and Tarell or between myself and the characters in his piece, I knew this piece. I felt like I’d lived a lot of it. That’s because, in the end, Tarell and I were two boys growing up in the same neighborhood, almost on the same block, and that both our moms went through a very particular ordeal with a very particular drug at a very particular time, which is something that a lot of us can probably say these days, even if the neighborhood or the block were a few streets over or a few states up. I saw the play, and I was just overwhelmed with feeling for these kids. This empathy I felt for them…

For the kid you once were…

Well, it’s not me, but it’s a world I know. It’s a world I lived in, for sure.

Shortly before he passed away, the author John Updike said, "The only reason to tell stories or to read stories is to generate empathy." Does that resonate for you as an artist?

I approached this whole piece, Moonlight, from that perspective. I wanted to very actively and deeply access my own empathy, to create this path of empathy for these characters, this story, the artists I’ve been lucky enough to work with on this film. I wanted to create that kind of space. Empathetic, but actively empathetic.

Most of us are done with empathy as soon as we’ve felt another person’s pain. That’s it: mission complete. What do you mean by active empathy?

You know in life there are passive allies and there are active allies. There are people who are kind about what you do or who you are, there are those who are encouraging or are in some way supportive, and then there are people who feel you so deeply that they get in it with you. They become active, mobilized, and then you’ve really got something. For all of the similarities between Moonlight and the world I grew up in, making this film really required that I find my own empathy, and then to grow it.

In what ways?

Here’s an example: I’m straight. So when I look at this film, its source material is a play by Tarell McCraney and his sexuality is a key component of his work and a key component of this main character’s identity. In the beginning, I felt a little bit like, “Well, shit…Can I even take authorship of this?” Is this my story to tell? Because of a difference like sexuality is it even possible for me to take authorship? You have to find your empathy. You have to find the places that you connect with other people. Because there I am with this story that has turned me inside out, but there is this important aspect to this character that I, personally, cannot relate to. So what do you do with that? So you go back to when the Supreme Court passed the same-sex marriage bill and Facebook let everyone change their profile photo to that rainbow overlay, and I was, like, “That’s cute…” It’s cool, but it’s cute. It’s passive empathy. That’s being a passive ally.

It's like hashtags.

It is like hashtags, yeah, which definitely have their use and have their place in the world. Moonlight has definitely benefitted from hashtags, for sure. At the same time, I saw in Moonlight an opportunity to very actively employ empathy, to cultivate it, to expand it, to grow it, to invite change and feeling and growth into my own heart, and hopefully to do that for others with the film. But it had to be active. I didn’t just want to stir feelings in people. I wanted to make a film that would be active, that would be an active ally for anyone in the world feeling the things these characters feel, no matter where they are or who they are or what their circumstance. That was important to me.

How do you do that as a writer?

There are people who tell stories about certain issues or certain subsets of people, this or that, whatever “hot topic” might be in the spotlight at the moment, and they’re very talented and they’re very well meaning, and they’re working from a place of pure empathy. Beautiful. But there’s a ceiling on that. Moonlight originated with Tarell’s piece, this beautiful thing, and I thought that if I could preserve his voice and wed it with this empathy it inspired in me, we could get to a place where we had created something that was authentic and lived-in and true. That we could take all of this empathy, get active with it, and create something that might generate even more empathy. It’s working. It seems to be working. We’re playing in theaters now, and I’ve traveled all over the world to watch this film with all kinds of people, truly disparate groups of people from all walks of life, and wherever they are in the world, they seem profoundly moved by the experience of watching the film. Audiences are now connecting with the film in the ways that I did with the Tarell’s piece, the way the cast and crew connected with my screenplay, the ways that I always hoped audiences would. We made this film with a mission in mind, with passion and guts and empathy, and it’s kind of like a dream how it’s all playing out now.

In an era where common wisdom suggests audiences will only head to the multiplex for blockbuster bonanzas heavy on the eye candy, Moonlight is, decidedly, an odd bird. And yet, Moonlight is one of those films that plays exquisitely, like a campfire story, like a story shared between intimates. Watching this film surrounded by other people is an experience.

I know what you mean. I’ve had that experience. I hope I always have that experience watching Moonlight, especially watching it with other people. It’s interesting to me because Moonlight is not an intellectual film. Emotion is the bedrock of this piece. There are certainly a number of intellectual choices that went into making the film, some formal dynamics and stylistic choices that were very intellectually driven—casting different actors to play the same character, sound design, the visual scheme—but the intellect was always, always, always in service of the emotion, the feeling. It was about serving and honoring the feeling. What’s been really trippy is reading some of the reviews we’ve received from some tremendously talented critics. These are tremendous, sharp, intelligent writers doing excellent work, but somehow going beyond the intellectual rubric of writing a fantastic review. They’ve recognized and tapped into the feeling too, and that starts getting me emotional all over again.

Audiences seem to really connect with Chiron, your main character, despite the fact that they might not be African American, gay, Floridian, impoverished, and all the rest. He is a very specific character in many ways, and yet everyone can see themselves in him.

I know I could. I can. But here’s what it is: you’ve got a story about this kid dealing with these things, right? But you narrow it down, drilling it down just a little bit deeper, and the specifics of this kid’s life are no longer the predominant or overwhelming thing. Most audiences are not going to see Moonlight and relate specifically to the things this character deals with, but they really can see themselves in this character’s humanness. It’s this idea of the specific becoming the universal. You see Moonlight and you think, “If he is a person, then I am a person,” and maybe you’re changed a little bit. It’s just that simple.

That’s some elegant, audacious footwork there. It was only a few weeks ago that you first screened the film. Your first stop was Telluride.

That’s where we world premiered, yeah. I love Telluride. I’ve been there for every festival the last 14 years. It’s my home away from home, but it’s a very white place… And then beyond color, there’s a whole set of class dynamics, a whole other level. So there’s all of that going on, and I figured this is the perfect place to premiere this film. Most of the audience is going to have nothing in common with this character, but maybe by the end of the film they will. So the film plays there, and I’ll never forget this: about 30 minutes after the first screening, I’m walking outside the theater for a little open air, walking down this little pathway between these condominiums, and this older guy—this 65-year old, gray-haired white guy, wearing a North Face jacket is just standing at the other end of the path I’m walking, just staring at me. I approached him, and I was, like, “Are you alright?” And he just kept staring at me. He was just speechless. I put my arms around him. I just gave him this hug, and then this guy is, like, sobbing in my arms. He’d been in the screening. He’d seen the film. I cannot account for that. I do not know how that happens. All I can do—all any filmmaker can do—is try to get the characters right, get the story right, be truthful to this, be truthful to that, lend it your voice and your power and your light, and then whatever you do next… Hope. Pray. Whatever.

You do your best and then hope for the best.

Yeah, right. You cannot engineer that kind of response in people. That is something bigger than any filmmaker or any intelligence or any design or master plan. There’s no recipe for a film like Moonlight. That’s what I’m trying to say. Thank God there’s not, because I don’t know if I could resist it.

Casting different actors to fill the same role could have been gimmicky, a stylistic grab that flops, but it works superbly. Is that a choice the writer makes, or the director?

Both. I mean, it was a writer's choice for sure, but the seed for that was in Tarell’s piece. He describes his play as being circular, like a day in the life, basically. All things are happening all the time. The moments are not necessarily linear, but comprehensive, like the ways this moment sort of exists as an extension of or a response to or an escalation of moments before it. The day advances, but we drag every version of ourselves through it all, hopefully getting better and better as we go. I thought the best way to make that, cinematically speaking, was to cast three different actors in the lead role. Show this person completely at one stage of his life, and then show him almost completely different at another stage, then again, and you somehow get a feel for how the world has affected this person. And maybe he’s impacted the world, too. Maybe. It's a unique commentary on the character and the world at large at once.

You make it sound simple: a creative choice, plain and simple.

Well, I don’t know if it was simple or not. I know I thought it would be a challenge, for sure. As a writer, it was definitely a challenge. So I guess that all began with me as a writer, but I was writing for a director I knew—me. I knew the challenges I was having writing it, and I became increasingly aware of the challenges I could have directing it. That made it all really juicy, man. I was like, “I really want to pull this off.” And everybody who worked on the film, they just kind of leaned into it.

If Moonlight is about the ways the world can work on a man, the filmmaker you are today appears to be working in a world at least somewhat different than the world of 2008. Superficially, at least, the gatekeepers have softened to a broader spectrum of films, filmmakers, voices of diversity. Is that your experience as an artist?

You know, it's interesting, and there are a few layers to it. This is going to sound immodest, but I can’t tell you how many filmmakers of color have come to me through the years and said, “Man, I started making movies because of your movie.” That always just trips me out, but it’s an important thing to remember: you don’t always know who’s watching or how they might be moved or inspired. I just directed an episode of Dear White People over at Netflix. You know, Justin Simien created it, and he tells the story of seeing Medicine for Melancholy all those years ago and being like, “I have to finish Dear White People.” I'm like, "That doesn't make any sense to me!" But he says Medicine is what got him over the bump and inspired him to tell his story.

What other changes have you noticed?

This beautiful thing has happened over the eight years where I've kind of been on the sideline, doing these little commercials and short films and stuff. This is what’s happened: all of these other very diverse voices, these tremendous young artists, have been making work, consistently good work, better and better and better work. Watching Ava [DuVernay] over the last eight years has been amazing. I will never forget Sundance 2009. Ava had these two dinners where she invited a whole bunch of us out and she laid out the whole map of what she was going to do, how she was going to change the world, and here we are.

This is Ava’s world, and we’re just living in it.

Yeah! Here we are, eight years later, and it's all come to fruition. She has blazed that trail and it has cleared a path—at least a little bit—for a lot of very talented artists. I don’t know if it’s easier to do what I want to do now, but I no longer feel like my voice is going out into the world alone. Speaking purely about filmmakers of color now, there are now a lot of other voices presenting their stories in film. Nobody’s trying to tell the entirety of the Black Experience anymore. I mean, every now and then somebody tries, but there’s a ceiling on that too. You can’t make a film that says, “Here’s my declaration on this and what it means to be that.” Instead, you’re seeing filmmakers who, now that they are not alone, are finding the confidence and the courage and the support to tell more specific, more personal stories—Ryan [Coogler] with Fruitvale Station and Ava with Middle of Nowhere and Selma, Justin with Dear White People, Donald [Glover] with Atlanta, Issa Rae with Awkward Black Girl and Insecure. Everybody’s been marking the canvas, and there is this audience that recognizes something new is happening. “I didn’t even know there was a mark there!” It starts as a niche thing that slowly goes mainstream, so you get people going, “Oh yeah, I really like Awkward Black Girl. Maybe I’ll go check out this Moonlight thing next weekend.”

Is that a shift primarily in the artists, or is that a shift in the culture at large?

Ava's plan was that she was going to make lots of work, work that she cared about, and she was going to create a network, a firm, a system, to support other people's work that she cared about. That was the plan. The whole thesis was: if we create the content, the content will manifest an audience. And that’s exactly what’s happened over the last eight years.

What advice do you have for up-and-coming writers?

It’s not going to be a writing thing; it’s going to be a reading thing. Read screenplays. Read screenplays. Read a lot of screenplays. You have to. When I finally did film school, I did like a year—and then I stopped the program. I took a year off. I read scripts. I watched a lot of movies, mostly foreign films. I got a subscription to Sight and Sound. I took a film and photography class. I wanted to ingest what I thought was the very best version of what I was trying to do. So I read everything by Robert Towne and Charlie Kaufman—two totally different approaches to screenwriting, equally brilliant. I still read screenplays all the time. Michael Haneke’s Amor? That is crazy, crazy, crazy good. But if you’re really looking for a script to start with? Read Her. If I was a new writer, I’d read Her. A thousand times.

© 2016 Writers Guild of America West