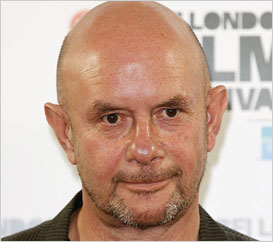

Nick Hornby’s Wild Ride

Bestselling British author Nick Hornby might not seem the most obvious choice to adapt Cheryl Strayed’s grief-stricken memoir Wild, but the novelist explains why he feels a deep connection to her redemptive story.

Nick Hornby

Nick Hornby

When I'm messing around on Facebook in my undies, I have to think to myself, God this is a very privileged life to be living.

The protagonists in Nick Hornby’s expansive oeuvre—which spans memoir, novel, essay, criticism, and rock & roll lyrics—are often lost, literally and figuratively, having somewhere along the way strayed, bottomed-out, or flopped existentially akimbo, yearning then to discover something they’ve never known before: peace. Since his 1992 debut, Fever Pitch, an autobiographical book about the author’s almost desperate sports fanaticism and romantic longing (turned into a British film with Colin Firth in the 1990s, then remade in America in 2005 with Jimmy Fallon as Hornby’s big screen surrogate), Hornby has carved a formidable, bestselling niche for himself as a master chronicler of contemporary ennui, bewilderment, and ache, conditions his heroes frequently treat with heavy doses of pop cultural triage and junk food distraction. (Don’t miss High Fidelity, About A Boy, and A Long Way Down, all of them adapted for film by other screenwriters).

In Wild, based on Cheryl Strayed’s chart-busting reminiscence of her grief-stricken, ultimately redemptive 1,100-mile solo hiking trek up Pacific Coast Trail after her mother’s sudden death, the 57-year-old Hornby both honors and expands the delectable, profoundly moving source material. Though Wild’s main character—Strayed herself, played by Reese Witherspoon—is a 20-something American woman in the Clinton-era, the English screenwriter is right at home and under the skin of a character hungering for a new home in the world. In 2009, Hornby earned an Oscar nomination for writing An Education, based on journalist Lynn Barber’s memoir, and early buzz suggests he should dust off his tails for this year’s awards season as well. Whether Hornby’s invited to the parties or not, he still delights in his “day job,” recently publishing a new novel, Funny Girl, in England. U.S. readers will greet the book next spring.

You’ve worked in such a broad range of mediums and genre. Do they require different muscles?

No, not really. Sadly, it all seems to end up with me sitting on my own in a room in front of a computer. In the end, writing is writing. You just have to sit there and do the work.

There are some writers who believe in the muse, while others believe that writing is simply labor—nothing precious or magical, just a matter of doing the job. What are your thoughts?

Well, there is inspiration before the typing starts. Those are the times where the juices really get flowing, where you have an idea, and then that idea collides with another idea, and suddenly you know that you're going to have to do this thing and spend quite a lot of time doing it. But once you're up and running, then, you know, I'm not saying it's work like coalmining is work, but there's certainly no point in waiting for the muse to strike then. The muse has already struck, and you've got to get on with it.

If writing is merely work, it still beats a lot of other kinds of work, right?

It's funny, last week I was on a book tour in the UK, and one of the places that I read was a school in the center of Cambridge, where I used to teach kids. I was saying to the audience at the event, that in a 40-minute lesson, you could look at the clock after five minutes and think, Jesus Christ, there are 35-minutes left, and I have no idea how I'm going to get through them. To me, that’s hard work. I still think of those times. That was 30 years ago, but I still think of those times a lot. Sometimes these days, when I'm messing around on Facebook in my undies, I have to think to myself, God this is a very privileged life to be living.

Between Gone Girl, which she produced, Inherent Vice, in which she stars, and Wild, in which she does both, Reese Witherspoon seems to have some sort of diving rod for great source material these days, yes?

Well, she really can read! (Laughs) I met her a few years ago, when An Education was on the awards trail, and I was at a party, and we were introduced. The first thing she said to me, which I really wasn't expecting, was, "Did you write ‘Nipple Jesus’?" Now, ‘Nipple Jesus’ is a short story I wrote for a short story collection many years ago. If you'd asked me how Reese Witherspoon was going to finish the sentence, "Didn’t you write ‘dot, dot, dot’” I wouldn’t have come up with that piece in a million years. It made me instantly curious about her. She's kind of a book nerd. I mean that as the highest compliment, incidentally.

How did the job writing Wild come your way?

I chased them, simply put. I read the book, more or less, as soon as it came out, and when I finished it, I thought, “Oh, wow, that could be an incredible movie, and I need to find the people who have bought it.” When I learned it was Reese and that they hadn't made a deal with another writer yet, I said, “I want a shot at this.” Because of my experience with Reese—with “Nipple Jesus” and so on—she looked rather kindly upon my plea.

With all respect, a 57-year old Englishman is probably not the first writer considered for such a project.

One of the beauties of the book was that it didn't matter who you were, you're on that trail with this girl. Also, there’s so much art—and love of art—in this book: music, poetry, fiction, quotes, and such. You know, it's not really a book about nature. It's not a book about “look how tough I am that I got this done, and you can do it too.” It's about somebody who lives a kind of urban life and is suddenly in this situation where everything's falling apart, and the only way she can put it back together again is to go on this hike. I really connected to this, and her compulsion, actually. There's a kind of genre of book that I really happens these days a lot and it always begins with people saying, "So I decided to do this crazy thing." Actually, they never say it; they just kind of go out and do it and then you inevitably learn that most of these people only did the crazy thing because they thought whatever “it” is would be a pretty good idea for a book. Wild is the opposite of that. What Cheryl Strayed did in 1994 wasn’t about deciding to do some crazy thing so she could write a book about it; there were just no other choices left in her life. She did what she had to do. In terms of tone, Cheryl’s book reminded me so much of Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, and that’s an album that I connect with very, very deeply.

Music is key to so much of your work, including the lyrics you write for Ben Folds and Marah. Do you listen to music while writing? Is there a Nick Hornby/Wild playlist somewhere out there?

No, no, no. For Wild, I took my cues from Cheryl and her book. She has such an appreciation and love for music, and her writing is actually quite musical. With the voiceover for the film, what we really wanted to do was capture that sound, the actual contents of her head, where it begins with this jagged, fragmented stream of curse words and old bits of advertising and lyrics she remembers and, by the story’s end, has become something more closely resembling what most of us would call a traditional cinematic voiceover. There is, hopefully, a certain musical aspect to that.

Interestingly, you are an author who has had his books adapted for film by other writers, and now you’re a writer adapting other peoples’ books. Is there any sort of karmic concern here? What’s the key to adapting the work of others?

Well, for one thing, I don't want to adapt my own books. I would much rather use the opportunities I have in film to do something I haven't done before, and to work with people I haven't worked with before. Certainly, part of that is having access to somebody else's imagination. That seems to be the real gift that you get with adaptation because, of course, I never try and write the same book twice, and I try and always push myself, but I’m still stuck with who I am, and the kinds of things I’m going to come up with.

With an adaptation, suddenly, you're given the contents of someone else's head, and I want to mess around with that—to play in that space. From that point of view, adapting other people's work, it seems kind of straightforward. You do your best to tell that story. When I give my books up for adaptation, I never feel hopeless about it. I've met the people that will be working on it, and I’ve liked them, and I trust them. I know that they never want to do a bad job. It's always their intention to try and convey the spirit of the book in the movie in some way, and that's good enough for me. It’s what I try to do when I’m adapting, and it’s what I believe others do when they’re adapting me.

Early in your career, you did adapt your book Fever Pitch for a British filmed adaptation. Twenty years on, do you have any advice for that Nick Hornby, Screenwriter?

Yeah, that was the only one of my books I did. It was my memoir. I hadn’t written a novel yet, and I didn't know if I was going to be offered any other work in any other medium. Ever. So, I certainly wasn't in a position to turn that job down. I like the movie. In retrospect, I wish I'd known that the film was actually going to happen, if you know what I mean. The one thing I can’t get over in film is that there always seems to be a very small percentage chance of the movie actually getting made, no matter how long or hard you work on it. In the book world, I'm at the stage in my career where, unless I screw up catastrophically, the book will still be published. But in film, it doesn't matter who you are or what the project is, there are always about a million things that can prevent it from being made. What I remember about Fever Pitch [released in 1997] is never really taking it very seriously. For years, it was: every two months or every year or so, someone would say, “Oh no, we're still going to make this, and would you do another draft, and would you try this that and the other?” It took a very long time, and I don't think I ever quite believed that those scenes I’d written would ever become a movie. Maybe I'd have written with more fervor if I'd known that it was actually going to happen.

In Cheryl Strayed’s book, she writes that her journey “had many beginnings.” This is not an ideal situation for a screenwriter. How do you approach a book like Wild, which despite its spectacular settings and vivid characters is also a very interior book?

What was really interesting for me is that the second time I read Cheryl’s book, I had a highlighter pen, and I highlighted the stuff that I would like to see on screen. When I was done with that pass, the first thing I noticed was that we could have made a really good two-hour movie that didn't involve Cheryl ever going on the trail. There was so much dramatic incident and conflict and pain in the backstory. There were a lot of good films in Cheryl’s book.

Tell me about writing the film you did make from Wild.

Well, you know right from the start, “Okay, half of this has got to go if she’s ever going to hit the trail.” So then you go into the trail stuff and that involves a lot of people Cheryl meets along her journey, and yet this is a film, really, about a young woman being on her own, so it was a constant fight for the room—the pages—to convey all of the flavors of the book that I loved the most: the tumultuous, complicated, populated backstory, the divorce, the family, the death. So you’re always negotiating with yourself to make room for one thing you love by sacrificing another thing you love—and that’s before you ever begin having the conversations with Cheryl or Reese or [director] Jean-Marc Vallee about the parts they love and want to see in the film. That’s the long way of saying: it’s a process of boiling things down. The marriage of incidents I chose for this screenplay were what I thought would become the best coherent whole. We had to be quite painstaking in the reduction. It was quite painful for me, personally. Jean-Marc was really good at pushing me to condense and condense, to put more and more of the emotional stuff in, and compactly so.

How closely did you work with Cheryl?

She was really trusting. The big thing was that she had formed a very close bond with Reese right from the beginning and, because she trusted Reese so much, Cheryl very quickly trusted her book—this vulnerable, honest chapter of her life—to the guy who wrote “Nipple Jesus.” Cheryl knew that Reese was going to make the most faithful version of the book possible, without being slavishly devotional to it, so Cheryl had great faith in the process. Along the way, I showed Cheryl drafts, and she was able to give technical advice on the hiking and that aspect of the journey, on what couldn't have happened, and how it would have happened instead. She was remarkably helpful in those ways. She never, ever said, “You're messing this up, buddy.” Though I guess there’s still time! Cheryl was a real joy to work with.

Looking over your work, there is a recurring theme, sometimes very loose, that in grave loss, we often go to radical extremes to rebirth ourselves. We’re lost inside, then we get lost on the outside, and then, somehow, we’re not lost anymore.

Or less lost, hopefully! Yes, writing Wild didn’t seem like a huge jump to me. Every story feels like joining up the dots and gathering your makeshift family on some sort of journey, doesn’t it? How could the guy who wrote High Fidelity write Wild? Well, I believe there have been a lot of signposts and dry runs along the way. My stories, as you pointed out, are always about trying to put yourself back together in ways that might actually improve upon the original. That might come up a few times in my work.

One of the changes you made in adapting the book is moving the mother-daughter relationship to the fore of the film. Tell me about that choice.

Well, yes, it becomes the heart of the film. That relationship actually kicks off the book, and you can feel on the page that Cheryl’s walk is fueled by all of this rage and pain. Cinematically, I didn’t know whether that was going to work or not, so I wanted to jumble it up a bit. It was important to me to establish that this woman was doing this thing from a place of deep damage, but with the audience not quite understanding, initially, what that damage was. I wanted a bit of emotional mystery, I guess, so we reveal the backstory sort of backwards as the walk goes forward. At least that’s the way I imagined it.

This raises the question of structure and planning, outlining. From a craft standpoint, how do you get this work done? Is it a stack of carefully organized index cards or a “serial killer wall” with thumbtacks and color-coded yarn or…?

I had a bunch of cards—mostly just to remind myself of where I was going. I'm not terribly organized—externally anyway. So the cards helped give me the sense of, “This is where you’re going. You’re not lost. Just keep going toward that.”

You’ve had a longstanding, uh, relationship with one of your producers, Amanda Posey. She’s your wife. How does that fuel or inform your screenwriting process?

I guess one of the reasons that we're together, or that any couple is together, is that we have similar tastes. We like the same kinds of movies. We want the same kinds of things from stories. So creatively, it's really easy to work with somebody like that. That’s a good place to start. The hard thing about being married to your producer is all the business stuff, because there are some days where she's gone off to try and get financing on a script and she's been turned down and when she comes home and I ask, “How was your day?,” she has to lie quite a lot of the time. “Oh, it wasn't so bad,” and all that kind of film business circumlocution has to be used in “difficult” times like that. We’re always having to support or coach each other through that “standard rejection letter” thing writers get from publishers. There are always a lot of “no’s” in the film world. If we weren’t married, and I were just the film’s writer and she were just the film’s producer, there probably wouldn’t be very much to talk about and I wouldn’t see her for six months at a time, and then, maybe, the film would get made. When you see each other every day, it can get more complicated than that. You’re on this crazy ride together.

In the world of books, you’re still a one-man band. It’s been a while since your last novel, Juliet, Naked, but Funny Girl is coming soon to the U.S.

Yes, and it just came out in England. What I wanted to write about was collaborative work, and so there are bits and pieces of the work I’ve been doing these last few years, the work in cinema. It’s also about the birth, life, and death of a fictional sitcom in the 1960s, and the writers and directors and producer—the team—that has to work through all of that. It really stretched the limits for me because I started the novel at a time when I was frustrated with what was going on with all of the various film projects I was working on. I thought to myself, “Well, I can put all this frustration into a dream of collaboration that's happening on the page in front of me, rather than not happening out in the so-called real world.” That’s how Funny Girl started.

So which is more harrowing: Cheryl Strayed's 1,100 mile journey on the Pacific Coast Trail, or Nick Hornby’s adventures in Hollywood?

You know, I really don't feel as though I work in Hollywood. Wild is really my first American movie, but the director’s French-Canadian and a lot of the cast and crew are from around the world. Only Reese was Hollywood, really. Wild was done outside the studio system. Reese didn't want to show the script to a studio until we were all happy with it, so [we] could then say to a studio, “Look, this is the film we're going to make. Do you want to fund it or not?” She was not interested in compromise. Even with that kind of idealism and position, there’s always a lot of fear. We were all worried that somewhere along the way someone at the studio would say, “Sure, we’ll fund this, but she can’t take heroin, and she can’t sleep with other people. No one wants to see that Reese Witherspoon movie.” So we kept Wild an independent movie right up until it was time to shoot, pretty much. In that regard, I feel like I still haven’t really had a “Hollywood experience.” At home, I work in British independent film. I’m not really a writer for hire. I don’t do rewrites. I’ve never written a big movie for a studio. I can’t really see any of those things happening, nor do I particularly want them to.

Still, someone’s probably taken your tuxedo to the dry cleaners with awards season now upon us.

You know that expression “fuck you money”? it's really a good expression in my particular case. Writing film is not my day job. I write books. I mean, I guess one could argue that I've now got two day jobs, and certainly writing films can be a good living. I just don't need to do any stuff that I don't really want to do, and I can't imagine being persuaded, which makes me, I’m sure, a very fortunate man.

© 2014 Writers Guild of America West