The Powers of Two

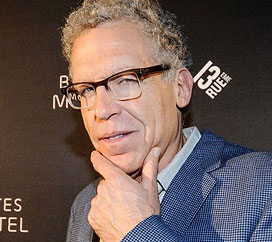

For most writer-producers, the prospect of running one show is daunting at best, so how does Carlton Cuse manage three? The creative force behind Colony, Bates Motel, and The Strain says collaboration is the key.

Carlton Cuse

Carlton Cuse

For me, the idea of working on multiple shows at the same time is just adrenalizing. I like the shifting gears and moving back and forth between different stories.

Carlton Cuse once revealed his personal ambition to “be as cool as Sawyer,” the golden-hearted, sharp-tongued, Byronic antihero on Lost, a landmark television series Cuse ran for six seasons with Damon Lindelof.

At 56, Cuse laughs when reminded of the statement, but doesn’t dismiss it either. And here’s the truth: if the brooding con artist called Sawyer, as played by Josh Holloway, currently starring in Cuse and co-creator Ryan J. Condal’s Colony on USA Network – can be said to have achieved any sort of redemption on Lost’s mysterious island, it most certainly arose from a faith and philosophy fundamental to the man who frequently wrote him. For Cuse always – and for Sawyer, ultimately – relationships are everything, collaboration is key, service is vital.

When Cuse was a new Harvard grad considering a leap into the entertainment industry, it was Ivy League classmate Hans Tobeason – and fellow Harvard alum George Plimpton – who helped make Power Ten, a documentary about the university’s storied rowing team. When Cuse arrived in Los Angeles looking for work, his storytelling resume exactly as long as Power Ten’s running time, it was the encouragement and support of established filmmakers like Bernard (Sweet Dreams) Schwartz, Michael (Crime Story) Mann, John Sacret (China Beach) Young, and Jeffrey (Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade) Boam that helped the rookie develop his voice, learn the ropes, and eventually leave his mark with series like The Adventures of Brisco Country, Jr., Nash Bridges, and Martial Law. Being mentored like so is a gift Cuse continues to cherish, his longstanding contributions to the Guild’s Showrunner Training Program only one of the ways he strives to repay the kindnesses once extended to him.

It was in the early aughts, though, that Cuse cemented his place in the television firmament, as well as his almost fundamentalist belief in creative collaboration, teaming with Damon Lindelof to run ABC’s Lost for six seasons. During the series run – an operatic comic book saga that merged survivalism and surrealism, kink and heroics, profound moral quandaries and boundless mystery to become a genuine pop culture phenomenon, Cuse and Lindelof became one of TV’s great bromances, a dynamic duo that not only created terrific television, but actually really loved and respected one another. Together, the pair negotiated with ABC a series end date for Lost, which enabled them to write toward the ending they always intended, a liberty many showrunners today now resultantly enjoy.

Though F. Scott Fitzgerald once famously opined that there are no second acts in American lives, Cuse’s work ethic, creative spirit, and devotion to teamwork could not keep him home, reciting lines of Sawyer’s dialogue into a bathroom mirror for the rest of time. Instead, Cuse leaped at the opportunities Lost generated for him, professionally, currently running three basic cable series – Bates Motel, The Strain, and Colony, currently airing on USA Network – and developing a fourth, Jack Ryan, based on the Tom Clancy novels. He also wrote last summer’s blockbuster, San Andreas.

It is with this commitment to storytelling, to encouraging in practical, measurable ways the next generation of writers, in establishing himself as a purveyor of stories across genres that all seem to say we’re much better off living together than dying alone, that Carlton Cuse has probably achieved what he once intended: he actually is as cool as Sawyer.

As it turns out, Lost wasn’t really about solving sci-fi mysteries, was it?

That’s one question about the ending of Lost that I’ll always be happy to answer. I’m not sure what else I can say to audiences who still want information about the polar bears. No, what Lost is really about are these people who are sort of lost in their lives and seeking redemption and what's meaningful who are forced, under these circumstances, to figure out what really matters in life.

With tongue in cheek: Are we talking about Lost, Bates Motel, Colony, or The Strain here?

There's probably a bit of a common theme across the different projects I’m involved in, which is true for a lot of writers and showrunners. I mean, in case of The Strain, the vampire apocalypse that overruns the city definitely forces people to figure out what matters most in life. In Colony, you have people within Los Angeles whose lives and freedoms are upended by an alien invasion. I guess as writers we all gravitate to certain themes, and they're reflected across our work. I would say, though, that I really start from a place of story, not a place of theme. Hopefully, theme is revealed to me – and audiences – as the story unfolds. Writers are influenced by the world in which they live, and the stories that we tell are ways of working out what we're seeing, feeling, and thinking about the world that we live in.

A lot of writers believe theme should precede story, but you work the other way around. How does your process – story first, theme later – work on a show like Colony?

Well, “story before theme” is just a hard and fast rule, like “theme before story” – until you break the rules! Colony actually started out, conceptually, a little bit more thematically. [Series co-creator] Ryan Condal and I, we're kind of fascinated with these images of Parisians in World War II under Nazi occupation kind of trying to go about their lives – sitting inside the cafes, drinking espresso, while Nazi storm troopers were going by. This idea that in a situation like that you had this broad swath of people in the middle of the Nazis and the Resistance who were really just trying to figure out how to survive, we just felt like it would be interesting, thematically, to explore the compromises involved in figuring out how one survives under such extreme circumstances. People ask the same question about when people write songs: Do they write the melody first or the lyrics? Different songwriters approach it different ways. As a writer, for me, if there's something in the story to latch onto, then theme gets revealed and you use the revelation of theme to amplify the story that you're telling. The thing I think about first is: What kind of a story, book, or character would be potentially interesting to me. Then, as I start to explore that character and the story he or she presents, the theme becomes clear to me.

With Lost, you and Damon Lindelof really changed so much of the television landscape, including the ways in which you fixed the series end date several seasons early and also negotiated several shorter seasons. Today, a 13-episode season is not uncommon. One might figure that would give a showrunner a bit of breathing room, but you’ve got four series going almost simultaneously. What’s wrong with you?

Yeah, I basically counteracted the move to shortened seasons by just increasing the number of shows! What can I say? For me, the idea of working on multiple shows at the same time is just adrenalizing. I like the shifting gears and moving back and forth between different stories. I find that I'm energized by having different stories that I'm working on at the same time.

Sometimes when you're under the hood of a car, you “accidentally” figure out how to fix the motorboat that's been in dry dock for a while, right?

That's a good analogy, yes. I have different offices for each of my different shows too, so when I go out to one office, I'm really focused on that one show, and when I’m at the other office, I’m centered on that show. For me, shifting gears mentally sometimes helps unlock new creative ideas or helps problem solve. Usually, the mental gears for me shift while I'm driving between the offices. That’s where a lot of the good ideas come from for me. I find it rejuvenating. Sometimes, if you’re only working on one show, you get stuck in your story a little bit, and if there’s only one show you’re doing, you can feel really stuck as a writer overall. I don’t really experience that, because there’s always a different show and a different set of “problems” to solve. It’s also important to say: because these are cable shows, they're not all happening all at the same time, which is really helpful. They’re not all on the same cycles. For example, Colony is essentially finished right now and it's airing and I'm working on upcoming seasons of The Strain and Bates Motel.

Organizationally speaking, how do you keep track of all the shows you’re working on?

One of the things that's helpful to me is that I don't have one master office. I have three offices, and they're all along the Ventura Boulevard corridor in the Valley. They're close to each other, but when I go to the Bates office, I'm really focused on Bates. When I'm at The Strain office, I'm really focused on The Strain. That helps in terms of organization. Also, I have really great collaborators so when I'm at each of these offices, I'm talking to my wonderful partner Kerry Ehrin on Bates, Ryan Condal on Colony. I have some wonderful writers on The Strain, like Bradley Thompson and Regina Corrado and Chuck Hogan. The thing I love best about my job – and my life – is working with other writers collaboratively to come up with ideas and solve problems. That's how I spend most of my time. For me, the creative process is so enriched by those collaborations. It's much more enjoyable to me than just sitting down and facing the blank page by myself.

You’ve attracted some spectacularly happy collaborations. As writers, we don't typically find our collaborators on E-Harmony or Match.com, so what’s the secret to finding a great collaborator and keeping that teamwork in a positive space for six seasons, like you did with Damon Lindelof on Lost?

It really depends on who you are. There are some writers who really enjoy working alone and like that solitary process of creation. For me, I know I’m better – and happier, and maybe the two things are related – in collaboration. There's a wonderful book called Powers of Two by Joshua Wolf Shenk. It’s so great. He talks about a lot of the things that we think of as singular collaborative efforts, and how they were really done in collaboration. Even people who sort of tower individually, like Einstein or Martin Luther King, had profoundly important collaborators to help them do that work. I look around at the landscape of movies and television, and for my money, the best director in movies is a duo – the Coen Brothers – and on television, you have teams like D.B. Weiss and David Benioff on Game of Thrones. With Damon, I had given him his first job years earlier on Nash Bridges, and we just hit it off and connected. Like with any relationship, there's just a fundamental chemistry to it. Damon and I just had this great aesthetic compatibility. By far, the most enjoyable part of Lost across the six years of making it was working day to day, hour by hour with Damon. We worked monastically 60-80 hours a week, 50 weeks a year to make that show, and I felt like the whole experience was so enriched by the collaborative process. In a show about relationships, the relationship between Damon and I was really the backbone of that show.

Some writers would fall ill at the very suggestion of that kind of intense, ongoing collaboration.

All I can say is: it's the way I like to work. I've tried to continue that process on my other shows. I have a wonderful collaboration with Kerry Ehrin, who's a beautiful writer who has done just amazing writing on Bates Motel and brought life and dimension to the characters on that show in ways that I never could have. I feel the same way about Ryan Condal on Colony. This weird sort of subversive take on alien invasion show was so much the product of hours and hours of conversation with a guy who's just really smart and creative. As I get more experienced in my career, I've come to focus attention on the things I find most important to me and on finding the situations that are going to be most rewarding for me. To me, that's it. And for me, collaboration answers both of those pursuits.

On Colony, you’re writing for Josh Holloway, an actor you know very well. How does that impact your creative process? Was Colony always written towards Holloway, or were the scripts “cozied up” for him later?

I know Ryan and I are not the only writers who have done this, but you create a show like this and it ends up being a giant role of the dice. When Ryan and I started breaking the Colony story, we found ourselves almost in unison calling the lead character [eventually dubbed Will Bowman] Josh Holloway. At the end of the day, we realized, we’d really better figure out how to get Josh to do the show! It’s something that I tend to do when I write; I often see the ideal version of the actor. I see that person – a certain actor – in my brain and it helps me write the character.

Obviously, you landed Holloway for the series, but how does his casting impact the show you’re making?

Sort of willfully, Ryan and I decided to play the long odds that existed that Josh would be available and interested to do the show. In the entertainment business, they always tell you, “You have to be good, but you also have to get lucky.” It’s true. In this particular case, Josh’s prior series (Intelligence) didn’t work out and he happened to be available. He was looking around. So when Ryan and I finished the Colony script, we sent it to Josh. He was being courted by a lot of other people, and the good news is that Josh felt as good about the collaboration we’d had on Lost as I did, and he said yes. I can’t tell you how much it means to me that we shared the same feelings about working together because to me, one of the primary responsibilities of a showrunner is to develop a trust and a bond with your actors, and it has to be a mutual thing I think. They have to trust you to do your job, to write greater material for them to play, and you have to trust them to take your creation and breathe life and vitality into it. It takes a while for that trust to develop, where you each understand what the other does and how the other person works, and Josh and I already had that. We had that shorthand. We already knew how that all works from Lost. I think that gave him the comfort to say yes to Colony, and I never had any doubt at all that Josh could not only do everything the story asked him to, but that he’d do it better than we’d written it. He’s really good.

Looking over the shows you’re doing right now, there’s a “prequel” to Psycho, a vampire story, an alien invasion story. On paper, these sound like suicide missions. There couldn’t possibly be anything new to do with these stories, right? Except you are doing new things with these stories.

Well, I mean that's the criteria, right? If you work, as I do, in the genre space, then the trick is to figure out if there’s something new to say. Is there a new take or a new approach to the material? In the case of Bates Motel, Kerri Ehrin and I subverted the mythology of the original Psycho movie. We didn't ever see Norma Bates in the Hitchcock movie, but it was implied that she was this horrible shrew who berated her son into going crazy. We decided, "Well, what if Norma was actually this funny, wonderful, sympathetic woman?" She may be a bit crazy as hell, and she’s got this son who has this flaw in his DNA and her smothering affection ultimately helps catalyze his transformation into this monster, but what if it starts off from a relationship between mother and son that is very different than previously implied or than any of us had really imagined it? That was interesting to me. The story ends up becoming a tragedy, a romantic tragedy. That was completely different than what is suggested in the original movie. That was what made it interesting. Also, making it contemporary, taking it out from under the shadow of the future, was key for me. Adding up all of those elements, it made it worthwhile to do it. To just sort of slavishly be living in some sort of period prequel to a classic movie that completely aligned with what happens in the movie, there isn't any good reason to do that. You're just going to be treading water creatively. You're going to be swamped by how amazing and how perfect that movie is.

How about tackling the vampire genre, which many feel has already overstayed its welcome with so many fanged stories in the last decade?

Well, I was really interested, like any sane person would be, in the idea of collaborating with Guillermo Del Toro. Not only did he write The Strain Trilogy of novels, but I knew he’d also do amazing work with the monsters. If you're doing a monster story, you’d better have a great monster, and Guillermo, I knew, would be good for that. Also, I loved that in Guillermo’s books, the vampires, they were actually very, very scary. They were these parasitic bloodsucking creatures. There was nothing romantic about them. They weren't brooding, handsome dudes with girl problems. It felt like, "Here’s a chance to do a vampire show that's really about scary creatures, not about who’s going to end up with a girl.”

So coming full circle, as Lost wasn’t really about solving this mystery or that plot point, Colony isn’t necessarily about bogeymen from outer space.

That’s right. It just felt like, "Okay, if we take this approach and make it an espionage story about a family struggling to survive, give it a science fiction backdrop, then that's vastly different than the traditional alien invasion show." That made it worthwhile to tell for me. That's really the criteria that I always apply to projects I’m considering: What's going to make this feel different from something that we've already seen?

Lost was one of the first shows that fixed its end date instead of being axed mid-story by the network or running several seasons too long, well after story has been exhausted. With Bates Motel and The Strain, you've announced similar plans, five-season runs. That’s fairly revolutionary and ends up allowing a television showrunner the same creative ground a screenwriter or a novelist might enjoy – you’re guaranteed the opportunity to end your story the way you want to.

Yeah, when Damon and I negotiated the end date of Lost, it was unprecedented. There hadn't been a network show that had ever agreed three years out on an end date. We negotiated a three years to the end of the series deal, and it was really critical to us, because that story had a beginning, middle and end, and we wanted to get to the end while people still cared about the show. The normal model in television at that point in time – and, in a lot of cases still, is like the Pony Express – you just ride the horse until it drops dead beneath your weight. That's fine if you're doing a franchise show like Grey's Anatomy or Law & Order, which could literally run forever. But Lost was a story with a beginning, middle and end, and we wanted to be sure that we could tell the end.

How does that impact you as a writer? We know that you and Lindelof were able to end Lost the way you wanted to, but how does knowing your end date affect your creative process, your storytelling, on a show like Bates or The Strain?

It's massively important. For Kerri Ehrin and I on Bates, we mapped that five-year journey very early on. We do not intend on ending the series in exactly the way fans of the Hitchcock movie might think we will, but we’re moving toward a very interesting intersection with the movie. Our story will have its own ending, but it will involve and intersect with some of the mythologies in the film. We knew that that was really a five-year journey, and being able to call our own ending was really one of the great creative reasons to do the show for me. If you think of the story of any television series like the letters of the alphabet, it's really fun to write the letters – you know there are always only 26 of them – and it's really fun for the audience to see that part of the story, to really ride the crescendo and anticipate an ending that’s always drawing nearer. I mean, look at the enthusiasm that arose for Breaking Bad as they were getting near the end of their alphabet. The audience wants to know what's going to happen. They want to know what is the fate of these characters. What is the resolution of the issue at hand? In the case of The Strain, will humanity survive this vampire apocalypse? That's a question that needs to get answered. If they do, or how they do, needs to get explored. That journey will become tiresome without an end date. I have to say: executives in television have also come to recognize the importance of this also. In a cultural environment where there are 409 television shows, when a network executive and an audience make an investment in a show, I want some sense of when that investment is going to pay off.

You’ve mentored a good number of writers and showrunners through the years, including, of course, Damon Lindelof. Why is that important for you as a writer?

It's one of the things that I'm the proudest of is having helped a bunch of writers on the path to becoming showrunners themselves. That's something that I take great pride in.

Is that because artists like Michael Mann and John Sacret Young offered so much support and guidance early in your career?

I’d like to think I’d be supporting younger writers every way I can regardless, but the generosity that’s been shown to me through the years, it must influence the choices I make today. John Sacret Young, who created the show China Beach and wrote a number of really beautiful television movies and miniseries across the years, was a really great mentor of mine. He was incredibly inclusive, so I was officed at Warner Bros. near him, and we were working on a couple of projects together while he was doing China Beach. I found myself sitting in on meetings on that show and watching his whole process producing the show. I learned a tremendous amount about showrunning, just by osmosis. John really taught me the value of being open, being inclusive with other writers, with being a team of collaborators, and that's one of the things that I really try to do. If you’ve never really mentored or been mentored, you’ll be amazed at how much both sides of the equation benefit and learn from each other. It’s one of the reasons why I’ve taught in the WGA’s Showrunner Training Program every year – since its inception. It's a wonderful opportunity to work with writers who are on the cusp of running their own series. By trying to answer the questions of writers on the verge, by trying to help them problem solve, you end up finding new ways of approaching your own creative problems. It’s amazing. Everybody wins, really. The truth about running a TV show, at least when you do it for the first time, is it’s kind of like being hit by a bus. Now, I can tell you that and you can probably imagine what its like to be hit by a bus, but unless you are actually hit by a bus, you’re probably going to get it wrong, at least a little bit. Part of what we do in the Showrunner Program is to try to prepare people to get hit by the bus. Are there ways, maybe, to not get hit by the bus, to not get run over, but maybe you can jump on the front of the bus, climb up the top, rip the top open, drop down inside, and take the driver’s seat? I really enjoy doing that.

© 2016 Writers Guild of America West