Members

The 101 Greatest Screenplays list was announced on April 7, 2006. The writing credits noted are based on that date.

Julius J. & Philip G. Epstein were twin brothers who had separate Hollywood writing careers until they became a team in 1938.

1. Casablanca

Julius J. Epstein

Julius J. Epstein

Philip G. Epstein

Philip G. Epstein

Howard Koch

Howard Koch

Some facts about the writing of the film:

• Julius J. & Philip G. Epstein were twin brothers who had separate Hollywood writing careers until they became a team in 1938.

• Howard Koch wrote the famous “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast that scared millions of Americans into leaving their homes, thinking the country was being attacked by Martians.

• 1940–Playwright Murray Burnett collaborates with Joan Alison on the play Everybody Comes to Rick's. The play is never produced.

• Dec. 8, 1941–Everybody Comes to Rick's arrives at the Warner Bros. Story Department.

• Jan. 6, 1942–Screenwriter Robert Buckner (whose credits include Jezebel and Yankee Doodle Dandy) sends a memo to producer Hal Wallis, expressing reservations about Warners' purchase of the play Everybody Comes to Rick's: “I might feel much freer in my opinions of this play, Everybody Comes to Rick's, if we hadn't paid such a sizable chunk of cash for it. Somebody must like it an awful lot and my criticisms will hardly be helpful to them. I do not like the play at all, Hal. I don't believe the story or the characters. Its main situations and the basic relations of the principals are completely censorable and messy, its big–moment is sheer hokum melodrama of the E. Phillips Oppenheim variety; and this guy Rick is two-parts Hemingway, one-part Scott Fitzgerald, and a dash of café Christ. Reading this back, I sound free enough, don't I?”–Warner Bros. archives

• Dec. 31, 1941–Producer Hal Wallis officially changes the title to Casablanca.

• The Epstein brothers finish their screenplay three days before the film begins shooting on May 25, 1942; Howard Koch completes his two weeks after shooting begins. All three writers were on call throughout the entire shooting period even though the Epsteins had been summoned to Washington to work on Frank Capra's Why We Fight documentary series. –IMDB

• The Epstein brothers and Howard Koch never worked in the same room at the same time during the writing of the script. –IMDB

• The Epstein brothers and Howard Koch never worked in the same room at the same time during the writing of the script. –IMDB

• Julius Epstein: “It doesn't matter how serious a film is... the right kinds of laughs can work in any film!”

• Howard Koch: “When we began, we didn't have a finished script...Ingrid Bergman came to me and said, 'Which man should I love more...?' I said to her, 'I don't know... play them both evenly.' You see we didn't have an ending, so we didn't know what was going to happen!” –Hollywood Hotline, May 1995

• Howard Koch: “The ending of the film was in the air until the very end... I was working every day on the set... I think we never really had the ending for sure... We thought of many possibilities and finally decided on the one that was in the film. That has proven to be the ending that the audience accepts.” –Hollywood Hotline, May 1995

• Julius Epstein: “Warner had 75 writers under contract, and 75 of them tried to figure out an ending!” –Hollywood Hotline, May 1995

• Leslie Epstein (son of Philip): “The true story is that while driving down Sunset Boulevard, the twins came to the red light at Beverly Glen (the city of Beverly Hills has yet to put a plaque on the spot); while they were waiting, they turned to each other and with one voice cried out, 'Round up the usual suspects!'” –Interview with Leslie Epstein, the American Prospect

• A staunch supporter of the Screenwriters Guild and other motion picture industry unions, Julius Epstein was investigated during the communist scare of the 1950s. When asked if he had ever belonged to a subversive organization, he responded without hesitation: "Yes–Warner Brothers." –obits.com

• In the 1980s, this film's script was sent to readers at a number of major studios and production companies under its original title, Everybody Comes To Rick's. Some readers recognized the script but most did not. Many complained that the script was "not good enough" to make a decent movie. –IMDB

Mario Puzo was broke when he signed a contract with Random House for his novel The Godfather.

2. The Godfather

Some facts about the writing of the film:

- Mario Puzo was broke when he signed a contract with Random House for his novel The Godfather.

- Son of composer Carmine Coppola, Francis Ford Coppola won the Samuel Goldwyn Award for best screenplay for Pilma, Pilma, when he was a student at UCLA. When he won the award, he was hired to write the screenplay for Reflections in a Golden Eye.

- While still a student at UCLA, he began his career working as an assistant to Roger Corman.

- A childhood bout with polio kept him bedridden for a year.

- Peter Bart at Paramount took an option on Mario Puzo's The Godfather before it was published, when it was still only a 20-page outline. Peter Cowie, Coppola: A Biography

- Puzo's book was a bestseller, selling 10 million copies.

- "In fact, the only person who knew less about the Mafia than Coppola was Mario Puzo, the rotund, kind-spirited novelist. 'Everything I know about "the boys" I learned from books,' he told me at our first meeting." Peter Bart, quoted in Coppola: A Biography by Peter Cowie

- Some of the characters in The Godfather were based on the "Five Families" of New York crime.

- While collaborating on the original screenplay, Coppola wrote "Clemenza browns some sausage." Puzo noted in the margin, "Clemenza fries some sausage. (Gangsters don't brown)." Peter Cowie, Coppola: A Biography

- The presence of oranges in all three Godfather movies indicates that a death or a close call will soon happen. The Senator is framed for murder after playing with oranges at the Corleone house, and Johnny Ola brings an orange into Michael's office before the attempt on Michael's life. Fanucci eats an orange just before he is gunned down and Michael is eating an orange (it looks like an apple, but it is an orange) while plotting to kill Roth. Plus, Marlon Brando as Vito puts an orange peel in his mouth prior to his death. Peter Cowie, Coppola: A Biography

- The Godfather was the highest grossing film in history at the time it was released. It is still one of the highest grossing films in history.

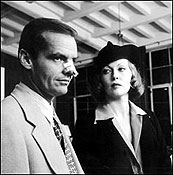

Robert Towne was born and reared in the Los Angeles area. He studied philosophy at Pomona College.

3. Chinatown

Some facts about the writing of the film:

- Robert Towne was born and reared in the Los Angeles area. He studied philosophy at Pomona College.

- Robert Towne based his famous exchange (Evelyn: "What did you do in Chinatown?" Jake: "As little as possible.") on a joke told to him by an LAPD officer friend. IMDB

- Jake Gittes was named after Jack Nicholson's friend, producer Harry Gittes. IMDB

- Robert Towne was offered $175,000 by Paramount to write The Great Gatsby in 1973. Instead he pushed to write a pet project of his, Chinatown, for the bargain price of $25,000. bbc.uk

- "The ending that I had originally conceived never ended in Chinatown. I had always felt it was really pushing the metaphor to end up in the physical location. There was one horrible day when everybody got crazy just about two weeks before shooting and somebody said, 'My God, there's no scene in Chinatown, and it's called Chinatown!'" AFI interview with Robert Towne

- "Originally, I had Evelyn [Mulwray] kill her father, and I had the detective try and stop her. In the first and second drafts he got the daughter out of the country. It also ended in a funny way: you knew that Evelyn was going to have to stand trial and you knew that she wasn't going to be able to tell why she did it. But it was bittersweet in the sense that one person, at least, wasn't tainted the child." AFI interview with Robert Towne

"With Chinatown, I originally thought I'd do a detective movie. That was all, initially. But then, I didn't want to do just any detective movie. Once you say you want to do a detective movie, you start thinking about what crime is to you, what it really means, what you think is really a horrible crime and what angers you. So I thought, I don't want to do a crime movie about the kind of things that don't anger me. I wanted to do something that really infuriated me. The destruction of the land and that community was something that I thought was really hideous. It was doubly significant because it was the way Los Angeles was formed, really." AFI interview with Robert Towne

"With Chinatown, I originally thought I'd do a detective movie. That was all, initially. But then, I didn't want to do just any detective movie. Once you say you want to do a detective movie, you start thinking about what crime is to you, what it really means, what you think is really a horrible crime and what angers you. So I thought, I don't want to do a crime movie about the kind of things that don't anger me. I wanted to do something that really infuriated me. The destruction of the land and that community was something that I thought was really hideous. It was doubly significant because it was the way Los Angeles was formed, really." AFI interview with Robert Towne

- "In the case of Chinatown, I wrote at least 20 different step outlines long, long step outlines, that got me about 70 percent of the way through it. Finally, after the 20th I said, 'Well, this is far enough. I know where it's going to end. Now, I'll just devote myself to the problem of writing it.'" AFI interview with Robert Towne

- "Chinatown is a pretty good metaphor for the futility of the good intentions. [Police officers in the film] are told to do as little as possible in Chinatown in the way of law enforcement, because you never know whether you're helping to avert a crime or helping to commit one." AFI interview with Robert Towne

- "We [Towne and Polanski] took the script and broke it down into one-sentence summations of each scene. Then we took a scissors and cut those little scenes and pasted them on the door of the study at his house where we were working. And the game was to shift those things around until we got them in an order that worked." Los Angeles Times, July 8, 1999

- "It seems like it took me forever to write at least 10 months. It was difficult; all screenplays that are highly structured are difficult you are not relying on the momentum of some picaresque tale to take you wherever you want to go. Always the hardest part of any story is to figure out the point of entry where your story begins." The Hollywood Reporter, July 2002

- For the most part, the final screenplay was shot almost exactly as it was written. "Once Roman and I agreed on the script, he held everyone's feet to the fire," Towne says. "Whatever disagreements we had, they ended when the script was written. Nobody said, 'Well, let's try it another way.' That was the way." Los Angeles Times, July 8, 1999

Orson Welles came to Hollywood in 1939, shortly after winning national notoriety at 23 for his audacious War of the Worlds radio broadcast, so realistic it scared the wits out of the audience and caused thousands to flee their homes.

4. Citizen Kane

Some facts about the writing of the film:

- Orson Welles came to Hollywood in 1939, shortly after winning national notoriety at 23 for his audacious War of the Worlds radio broadcast, so realistic it scared the wits out of the audience and caused thousands to flee their homes. The script for War of the Worlds was written by Howard Koch, who later co-wrote Casablanca (#1).

- Herman Mankiewicz was the older brother of Joseph Mankiewicz (#5 All About Eve).

- Welles was 24 when he co-wrote Citizen Kane.

- Before coming to Hollywood in 1926, Mankiewicz was the drama editor for The New Yorker.

- For decades, there has been controversy over what each of the two writers contributed to the film. Both Welles and Mankiewicz had long tinkered with biographical stories that approached the subject's life from a variety of angles. multiple sources

- In his school days, Orson Welles wrote an unproduced play called Marching Song, the exploration of a public figure through the testimonies of the people in his life. IMDB

- Welles drew from his personal life for the script, and Mankiewicz drew from publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst's life, to flesh out the character of Charles Foster Kane. It was long rumored that what enraged Hearst most was the use of the word "Rosebud," which some have claimed was Hearst's nickname for his mistress Marion Davies' private parts. multiple sources

Mankiewicz wrote the first draft of the screenplay in about six weeks, and wrote much of his work from a hospital bed. IMDB

Mankiewicz wrote the first draft of the screenplay in about six weeks, and wrote much of his work from a hospital bed. IMDB

- Budd Schulberg on Mankiewicz: "Mankiewicz claimed credit for the concept, and in truth had talked to my father, the producer B. P. Schulberg, about doing a film on William Randolph Hearst before Welles's dramatic arrival in Hollywood." The New York Times, "The Kane Mutiny," 5/1/2005

- Schulberg: "Welles rewrote scenes to define Kane as less a monster than a many-faceted public relations genius, as creative as he is finally self-destructive." The New York Times, "The Kane Mutiny," 5/1/2005

- Welles claimed that William Randolph Hearst was not the only inspiration for Kane. Among others, Chicago financier Harold Fowler McCormick was also a model for the character, in particular his promotion of his mistress and second wife, Polish opera singer Ganna Walska, who was considered a dreadful singer, despite the thousands of dollars McCormick paid out for her musical training. Another model was Samuel Insull, a Chicago utilities magnate and one of the founders of General Electric, who built what is now the Lyric Opera of Chicago for his singer/mistress. Howard Hughes was reported to be yet another model for the character, as was Time magazine founder Henry Luce. multiple sources

- Hearst, who had strong connections to the movie business, heard that he was the (or one of the) subject(s) of the film before it was completed, and tried to have the film suppressed and destroyed. It was rumored that he got access to an early draft of the script because Mankiewicz gave a copy to Charles Lederer (#31, His Girl Friday), the nephew of Hearst's mistress, Marion Davies. Frank Mankiewicz (son of Herman): "Lederer was a friend of Father's, but he was, in addition which my father knew very well Marion Davies' nephew, and my father gave him a copy of the script. Now, you want to talk self-destructive, I suppose that's a pretty good example. Lederer says he never showed the script to Hearst, but when it came back to my father, it was annotated, clearly by the Hearst lawyers, and I think that's probably how the old man learned that Citizen Kane was about him." The Battle Over Citizen Kane (PBS)

- When released, Citizen Kane was critically acclaimed but a box office failure, in part because Hearst allowed no mention of it in his newspapers, which made up the biggest newspaper chain in the country. The Battle Over Citizen Kane (PBS)

Joseph Mankiewicz was the younger brother of Herman Mankiewicz (#4, Citizen Kane).

5. All About Eve

Joseph Mankiewicz

Joseph Mankiewicz

Some facts about the writing of the film:

- Joseph Mankiewicz was the younger brother of Herman Mankiewicz (#4, Citizen Kane).

- His brother Herman, already a screenwriter, got him a job in Berlin in 1929 writing intertitles for silent films. He then became a "dialoguist" and then a screenwriter.

- The original short story "The Wisdom of Eve," by Mary Orr, appeared in Cosmopolitan magazine in May 1946, and was produced as a radio drama for NBC. IMDB

- The short story was based on a true incident Austrian actress Elisabeth Bergner (often called the "Garbo of the stage") told Orr about the 1943 Broadway production of The Two Mrs. Carrolls. A young actress who named herself Martina Lawrence (after a character played on stage by Bergner) stood outside the stage door for months wearing a red coat. Orr: "The girl lied to her, deceived her, did things behind her back even went after her husband " The New York Times, 10/1/2000, Vanity Fair, April 1999

- Joseph L. Mankiewicz: "They brought the girl inside, and she became the secretary. The play had closed down and they were recasting. When it came time to do a reading, she did the reading and even Bergner's husband, Paul Czinner, said she was remarkable. In her memoirs, Bergner says, 'Three weeks later [after talking to Orr], I was at the hairdresser and someone gave me a copy of this Hearst magazine, and there was the whole story I told Mary Orr.'" The New York Times, 10/1/2000

"After Orr dramatized the story as a radio play, it came to the attention of Mankiewicz, and he and [producer Darryl F.] Zanuck agreed it would be his next movie. The title was changed from The Wisdom of Eve to, briefly, Eve Harrington, then Best Performance, and, finally, All About Eve." The New York Times, 10/1/2000

"After Orr dramatized the story as a radio play, it came to the attention of Mankiewicz, and he and [producer Darryl F.] Zanuck agreed it would be his next movie. The title was changed from The Wisdom of Eve to, briefly, Eve Harrington, then Best Performance, and, finally, All About Eve." The New York Times, 10/1/2000

- Fox bought the story rights for $3,500 with no credit stipulations. Joseph L. Mankiewicz combined "The Wisdom of Eve" with a story he had been developing about an actress who recalls her life when receiving an award. IMDB

- Mankiewicz invented the "Sarah Siddens Award" for the film. In 1952, two years after the film came out, an actual Sarah Siddens Award was created, physically modeled on the one in the film. The 1967-68 Actor of the Year award was given to Celeste Holm, who played Karen Richards in the film; in 1973, Bette Davis (Margo Channing) was given an honorary Sarah Siddens Award. Los Angeles Times, 7/25/1999

- Star Bette Davis credited screenwriter Joseph Mankiewicz with saving her career by writing such a great character. Davis: "Mankiewicz is a genius the man responsible for the greatest role of my career. He resurrected me from the dead." moviediva.com

- Mankiewicz had been forewarned that Davis sometimes changed dialogue, but, he said later, " not one syllable is different on the screen than in the screenplay."

- Years later, Davis recalled Mankiewicz's description of Margo Channing: "He said she was the kind of dame who would treat her mink coat like a poncho!" Vanity Fair, April 1999

- Mankiewicz: "Male behavior is so elementary. All About Adam could be done as a short." moviediva.com

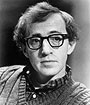

Woody Allen was born in Flatbush, NY. He has been a television writer, a playwright, a screenwriter, an actor, an author, a director and a producer.

6. Annie Hall

Woody Allen

Woody Allen

Marshall Brickman

Marshall Brickman

Some facts about the writing of the film:

- Woody Allen was born in Flatbush, NY. He has been a television writer, a playwright, a screenwriter, an actor, an author, a director and a producer.

- Marshall Brickman wrote jokes for Woody Allen's standup act in the 1960s.

- Allen originally conceived Annie Hall as a murder mystery with a subplot about a romance. multiple sources

- Woody Allen and Marshall Brickman considered as many as 100 possible titles for the film before settling on Anhedonia the inability to feel pleasure. United Artists fought against it (among other things, they were unable to come up with an ad campaign that explained the meaning of the word) and Allen compromised on naming the film after a central character three weeks before the film's premiere. The New York Times, 4/20/77

- Many elements in the script were based on reality, including the fact that Diane Keaton's real name is Diane Hall, and her nickname is Annie. multiple sources

Woody Allen: "Details are picked from life. I'm a comedian. Diane sings, and I'm friends with Tony Roberts, and almost everybody I know has moved out to California." The New York Times, 4/20/77

Woody Allen: "Details are picked from life. I'm a comedian. Diane sings, and I'm friends with Tony Roberts, and almost everybody I know has moved out to California." The New York Times, 4/20/77

- "In common with her character, [Diane Keaton] calls her grandmothers 'Grammy,' uses expressions like 'la-dee-dah' and 'Oh, gee, it's a wacky old world,' and orders pastrami and white bread with mayo." The New York Times, 4/20/77

- Marshall Brickman: "At first, in Annie Hall, we made Diane Keaton a neurotic New York girl, but the character had no dramatic transition. This led us to give her a family in Wisconsin." The New York Times, 8/21/77

- Brickman: "The first script of Annie Hall was much more episodic, tangential, and novelistic We started to become interested in the love story between Woody and the Keaton character, which was all over the place. We cut and pasted to make the love story more important, and the structure emerged. The material was telling us what to do." Film Comment, June 1986

- Allen on writing Annie Hall: "I've always been able to get laughs. I wanted to move on. This is not a quantum leap, but at least it's a couple of inches in the right direction." The New York Times, 4/20/77

Billy Wilder was born Samuel Wilder in Vienna, but called Billy by his mother. His grandmother, mother and stepfather died in the Auschwitz concentration camp. –multiple sources

7. Sunset Blvd.

Charles Brackett

Charles Brackett

Billy Wilder

Billy Wilder

Some facts about the writing of the film:

- Billy Wilder was born Samuel Wilder in Vienna, but called Billy by his mother. His grandmother, mother and stepfather died in the Auschwitz concentration camp. multiple sources

- Wilder was a reporter in Vienna and Berlin before becoming a screenwriter in Berlin. He came to the U.S. in 1934 to escape the Nazis. After learning English, he began working as a Hollywood screenwriter in 1937. multiple sources

- Charles Brackett replaced Herman Mankiewicz (#4, Citizen Kane) as theater critic for The New Yorker before coming to Hollywood in 1929. IMDB

- D.M. Marshman Jr. was a Time-Life reporter who played bridge with Brackett and Wilder. His credits include only one other film and some television work. multiple sources

- Sunset Blvd. was the last collaboration for Wilder and Brackett, after 14 years of working together. They had co-written Ninotchka and Ball of Fire, among other films.

- The original scripts were printed with the title A Can of Beans, because the writers were afraid the studio wouldn't support a script that might be seen as negative about the business. Their concerns may have been justified. When the film came out, MGM chief Louis B. Mayer reportedly screamed at Wilder: "You bastard! You have disgraced the industry that made you and fed you! You should be tarred and feathered and run out of Hollywood!" Variety, 7/19/93

- Brackett suggested the idea about a silent star's comeback. Marshman suggested the story could explore the relationship between a faded movie star and a young man. Variety, 7/19/93

• Incorporated into the script, "Young Fellow" was Cecil B. De Mille's nickname for Gloria Swanson when they worked together in the 1920s. Sunset Blvd. The Production, online analysis at www.geocities.com/

• Incorporated into the script, "Young Fellow" was Cecil B. De Mille's nickname for Gloria Swanson when they worked together in the 1920s. Sunset Blvd. The Production, online analysis at www.geocities.com/- Hollywood/Theater/6980/sbprod.htm

- Brackett: "Sunset Blvd. came about because Wilder, Marshman and I were acutely conscious of the fact that we lived in a town [that] had been swept by a social change as profound as that brought about in the old South by the Civil War. Overnight, the coming of sound brushed gods and goddesses into obscurity. We had an idea of a young man, happening into a great house where one of the ex-goddesses survived. At first, we saw her as a kind of horror woman an embodiment of vanity and selfishness. But as we went along, our sympathies became deeply involved with the woman who had been given the brush by 30 million fans." Charles Brackett in a talk called Putting the Picture on Paper

- The screenplay Norma Desmond is writing in the film was based on Oscar Wilde's Salome. IMDB

- Filming began before the final draft of the screenplay was complete. IMDB

- Wilder used the name "Sheldrake" in two other screenplays The Apartment (#15) and Kiss Me Stupid. IMDB

Paddy Chayefsky was born Sydney Chayefsky and grew up in the Bronx.

8. Network

Paddy Chayefsky

Paddy Chayefsky

Some facts about the writing of the film:

- Paddy Chayefsky was born Sydney Chayefsky and grew up in the Bronx.

- While recovering from a war wound in World War II, he became a writer.

- As one of the most important television writers during TV's infancy, Chayefsky brought special insight to Network, providing a scathing look at television.

- After leaving television in 1956, he wrote stage plays for Broadway as well as screenplays.

- Paddy Chayefsky on writing Network: "I still write realistic stuff. It's the world that's gone nuts, not me. It's the world that's turned into a satire." Time, 12/13/79

- Chayefsky on the "Mad as Hell" speech: "I wanted everyone, every man, woman or child to realize that they had a choice. I wanted them to know that they have the right to get angry, to get mad. They have the right to say to themselves, to each other, to the world at large, that they had worth, they had value. The speech wrote itself, because that was Beale's battle cry for the people." - Shaun Considine, Mad As Hell: The Life and Work of Paddy Chayefsky

The only music heard in the film comes from commercials and television show themes.

The only music heard in the film comes from commercials and television show themes.

- Chayefsky was on the set every day of shooting. IMDB

- Upon viewing the first cut of the film, MGM/UA execs sent Chayefsky a memo noting how many times expletives such as "ass," "son of a bitch," and a dozen or so other choice words were uttered by the actors. Chayefsky dismissed the memo and kept the language, saying that's how network types talk. All the expletives made it into the movie. In later years, Chayefsky said he wished he'd curbed the language some, that, upon further reflection, it was too much. - Shaun Considine, Mad As Hell: The Life and Work of Paddy Chayefsky

- "It's not that Paddy objected to people discussing his script-he just felt it shouldn't come from the guy in charge of business affairs." -Howard Gottfried, Chayefsky's producing partner (quoted in Mad As Hell: The Life and Work of Paddy Chayefsky)

- "This is not a satire; it's a documentary." -Norman Lear about Network (quoted in Mad As Hell: The Life and Work of Paddy Chayefsky)

- "I've heard every line from that film in real life." -Gore Vidal about Network (quoted in Mad As Hell: The Life and Work of Paddy Chayefsky )

I.A.L. Diamond – Born Itek Domnici in Romania, was raised in Brooklyn.

9. Some Like It Hot

I.A.L. Diamond & Billy Wilder

I.A.L. Diamond & Billy Wilder

Some facts about the writing of the film:

- I.A.L. Diamond Born Isidore Domnici in Romania, was raised in Brooklyn.

- "When shooting a picture, Wilder and his collaborator write on weekends at the studio, preferably on the set. The practice of weekend writing is pursued because Wilder has the unique theory that it is a mistake to have a finished script before shooting starts. He likes to feel free to change the script to make the most of any ideas that arise during filmmaking." The New York Times, 1/24/60

- Diamond on Billy Wilder: "When you've written with Billy and then go back to writing for a studio, it's like being traded from the major leagues to the minors. You'll have a scene written that would please anyone else and Billy will say, 'All right. Let's put this in the bank and see if we can get something better.'"

- Loosely based on Fanfaren der liebe (1951, Germany), which was based on another film, Fanfare d'Amour (1935, France). The German film features two desperate musicians dressing up as musicians and as girls. No gangsters are involved. IMDB

"You can't make this work, Billy. Blood and jokes do not mix." Producer David O. Selznick to Billy Wilder after Wilder described the project to him. Wilder called Some Like It Hot "a combination of Scarface and Charley's Aunt [the 1892 stage farce about cross-dressing]." Richard Corliss, Time, 10/30/2001

"You can't make this work, Billy. Blood and jokes do not mix." Producer David O. Selznick to Billy Wilder after Wilder described the project to him. Wilder called Some Like It Hot "a combination of Scarface and Charley's Aunt [the 1892 stage farce about cross-dressing]." Richard Corliss, Time, 10/30/2001

- Inside jokes: "Moviegoers of a certain age would also recognize a few old movie tropes, like the grapefruit George Raft starts to push in henchman Harry Wilson's face (as James Cagney did to Mae Clarke in The Public Enemy) and the coin-toss mannerism that young punk Edward G. Robinson Jr. affects. When Raft sees him, he asks sarcastically, 'Where did you pick up that cheap trick?' From the 1932 underworld classic Scarface, where Raft did it." Richard Corliss, Time, 10/30/2001

- Wilder: "Now we needed a line for Joe E. Brown and could not find it. But somewhere in the beginning of our discussion, Iz [Diamond] said: 'Nobody's perfect.' And I said: 'Look, let's go back to your line. . . Let's send it to the mimeograph department so that they have something, and then we're going to really sit down and make a real funny last line.' We never found the line, so we went with 'Nobody's perfect.' Cameron Crowe, Conversations With Wilder

- "The script for Some Like It Hot was not completed until four days before shooting was finished." The New York Times, 1/24/60

- Steve Allen attended a preview of the film in Pacific Palisades. He was the only person in a packed theater who laughed. A second preview was extremely successful. The Independent, 4/15/2001

- Wilder's tips #10 & 11 for writers: "10. The third act must build, build, build in tempo and action until the last event, and then 11. That's it. Don't hang around." Cameron Crowe, Conversations With Wilder

Well before The Godfather, Francis Ford Coppola had an interest in making a film about a father and son at the same age.

10. The Godfather II

Some facts about the writing of the film:

- Well before The Godfather, Francis Ford Coppola had an interest in making a film about a father and son at the same age. "In the father you see the potential of the son, and in the son you see the influence of the father," said Coppola. Peter Cowie, Coppola: A Biography

- The flashback sequences with Young Vito were part of Mario Puzo's original Godfather novel, but not used for the first film. Peter Cowie, Coppola: A Biography

- Puzo and Coppola passionately disagreed over whether Michael should have Fredo killed. Coppola agreed only on the condition that Michael would wait until their mother was dead. Peter Cowie, Coppola: A Biography

- The film, according to Coppola, was not meant to be a sequel in the traditional Hollywood sense; it was written as if it were part two of a novel. This influenced all parts of production even the same camera and lenses for the first film were used in the second, even though by 1974 they were less advanced technologically. Peter Cowie, Coppola: A Biography

- In an early version of the script, an ongoing story line was Tom Hagen having an affair with Sonny Corleone's widow. This was later discarded, but the line where Michael Corleone tells Hagen that he can take his "wife, children and mistress to Las Vegas" was kept. IMDB

- On the DVD, one of the deleted scenes shows Vito, Genco and Clemenza meeting in a shop owned by a "Signor Coppola." Clemenza asks if Coppola's young son, Carmine, will play them a song on the clarinet while they work. The boy comes in and plays them a song. This scene supposedly was written by Francis Ford Coppola in honor of his father, Carmine Coppola, who provided much of the music for the first two films. DVD extras, The Godfather II