Connect

Pandemic Past Is Prologue

A lesson from industry history on media consolidation.

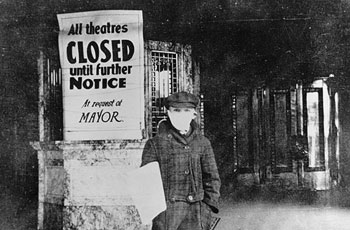

Theaters, like this one in Northern California, closed during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic.

Movie theaters have closed their doors. Production is shut down. Gatherings are discouraged. Everyone wears face masks. Workers are worried about their jobs, their industry, and the entire economy.

This was the scenario during the 1918–1919 Spanish flu pandemic, one that spurred the vertical integration of the nascent movie industry and created the powerful studio system of the 1930s and 1940s, where the biggest studios controlled every aspect of the entertainment business, from talent to production to distribution. A century later, media companies are once again positioned to leverage a public health crisis.

According to recent reporting, Amazon has considered buying the struggling AMC theater chain, which sustained a critical financial hit due to recent theater closures amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Such a move would likely be waved through by a Department of Justice with a pro-merger stance—the same DOJ that filed a motion in 2019 to terminate the Paramount Consent Decrees. These decrees were the result of several decades of investigations and lawsuits in the 20th century that led to a landmark Supreme Court case. The Court issued the “Paramount Decision” in 1948, forcing the largest studios to divest of their movie theater ownership and end other anticompetitive practices, effectively dismantling the old studio system. With the Paramount Decrees and antitrust enforcement generally now under attack, history stands to repeat itself.

In 1918, the head of Paramount Pictures, Adolph Zukor, saw opportunity in the disruption created by the Spanish flu and was in a prime position to take advantage of it. One of the most successful producers of his day, Zukor was known for popularizing block booking, the practice of forcing theaters to purchase packages of films containing cheaper, less desirable movies for the ability to exhibit first-rate films. The flu pandemic, alongside recovery from the war, created the conditions he needed to expand Paramount into the theater business.

Zukor had already been investigating the marketplace when he set out to acquire theaters which could not survive the long-term closures. To raise the capital he needed, Zukor convinced Otto Kahn of the investment firm Kuhn, Loeb & Co. of the potential that the movie business offered and, in November of 1919, $10 million of stock was issued on the New York Stock Exchange. This was the largest Wall Street venture in the industry to date, and other studios quickly followed. In interviews from the time, Zukor defended this investment and proclaimed that Wall Street would not control his business, despite the presence of bankers on his board. He also stated that he was not seeking a monopoly in the business. But he had done just that in creating the first vertically integrated studio.

It wasn't long before Paramount ran into antitrust issues and cries of monopoly and unfair competition, especially from exhibitors. In 1921 the first complaint was filed with the Federal Trade Commission against Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount-Famous Players-Lasky), for its block booking practices. After Zukor failed to comply with the FTC and the other studios expanded, the DOJ filed two antitrust cases in 1928 against the ten main members of the MPDAA (now MPAA). In 1930, the Supreme Court decided the case against the MPDAA, but by then more economic instability favored the big companies. The Great Depression had set in and the government decided not to enforce the decision in favor of keeping the entertainment industry aloft. Finally, in 1938, the Roosevelt administration filed suit against the Big Eight studios which eventually led to the 1948 Paramount Decision and the end of the vertically integrated studios. This resulted in a more varied marketplace where independent producers and exhibitors could do business alongside the big studios and freelance creative talent flourished for decades.

Zukor's vision lives on today, with ever-increasing media company consolidation, Wall Street investment, and numerous industry and economic structures that concentrate wealth and power at the top. There’s no telling how today’s pandemic, coupled with lax federal antitrust enforcement, will accelerate this trend.

The WGAW has urged the DOJ to keep the Paramount Decision as it stands, as one prong of the larger fight to promote competition. Great storytelling and successful writing careers depend on a competitive media marketplace with multiple buyers for writers’ work. The Guild continues to be an active part of the competition policy conversation, and will monitor events in the coming months and fight against the spread of monopolistic and oligopolistic practices.

Historical research for this article was conducted by Writers Guild Foundation archivist Hilary Swett.