Floating Weightless, Coming Home

Some might call Gravity science fiction, but Alfonso & Jonás Cuarón, the father and son writing team behind the new space thriller, describe the film as a metaphorical journey grounded in realism.

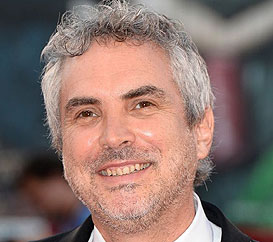

Alfonso Cuarón

Alfonso Cuarón

Jonás Cuarón

Jonás Cuarón

People call this science fiction but I like better the term ‘speculative fiction,’ where as a writer, you find a context that actually exists, a situation that actually exists and you speculate on the ‘What if?'

Let’s say that your father happens to be an internationally acclaimed writer-director. In fact, let’s say your father is Alfonso Cuarón, whose films include Y Tu Mamá También and Children of Men.

Now let’s say that your multi-award-winning dad reads one of your scripts and asks if you want to collaborate on another one. What do you do?

If you’re Jonás Cuarón (who happens to actually be Alfonso’s kid), you use the opportunity for a little filial criticism. “Jonás said, ‘Look, I like your films, I dig your films but you tend to have a bit too much rhetoric,’” recalls the writer-director regarding his son’s reaction.

Luckily (and perhaps wisely) this wasn’t a rejection. Rather, it was a proposal. “He had a theory that we should write a screenplay that was like a rollercoaster of a ride, where you're at the edge of your seat,” continues the veteran filmmaker, “but do that with an emotional journey that is complementing that ride. It's not about stopping the action to go into the emotional or vice versa; it's making one part of the other. And you link those two lines with visual metaphors – metaphors told through the moment – instead of stopping and talking about them.”

The result is Gravity, a taut thriller starring Sandra Bullock and George Clooney as two astronauts trapped in space when their shuttle is destroyed by debris. To call it a rollercoaster is an understatement.

Says the younger Cuarón of the project: “When you strip the narrative down, suddenly it becomes almost this virtual experience for the audience where, in the case of Gravity, the debris becomes a metaphor for the adversities that the audience is having at that moment. Where they can project all their stuff onto this character and the character becomes an avatar for the audience.”

Recently, the father and son writing duo spoke with the Writers Guild of America West website, in separate interviews about their collaboration on Gravity. While it’s destined to be one of the season’s best “popcorn flicks,” it’s not just Die Hard in earth’s orbit. Rather, this is a movie set in some seriously deep space.

How much of what we see in movie is feasible in outer space – and how did you go about researching that?

Alfonso Cuarón: When Jonás and I started writing, we wrote a quick structure and draft just more in terms of the movements of the film. I’ve always been a fan of space exploration, so we had the basics like the International Space Station, Chinese Station and so on. We finished the draft then we consulted with some space experts and that informed the rewrite. It's fiction, but in the frame of this fiction, we wanted to be as plausible as we could. So we consulted with them and that informed the next draft.

And did they point out anything that made you have to majorly rework your first draft?

Alfonso Cuarón: Not majorly. It was like silly things like we had a puncture in her suit and how they were going to fix it. He said, “Don’t even go there.” That couldn’t happen in the timeframe of the film. And it was actually a simple substitution because the whole point was this ticking clock, and she's losing oxygen. So we just transformed so she's already low of oxygen.

Jonás Cuarón: We did a lot of research because for us it was very important that this was a very realistic film. We didn't want it to fall into the realm of fantasy. We wanted it to seem almost more like a documentary gone wrong kind of experience, so like it took a lot of research and talking to astronauts to try to make it as close as possible. Still, you're a writer, so you know where you need to go from point A to point B, so even if an astronaut is telling you, "That's not possible," you have to take certain creative licenses. But still the idea was to try to find the best way for the situation that we're posing to happen. I mean people call this science fiction but I like better the term “speculative fiction,” where, as a writer, you find a context that actually exists, a situation that actually exists and you speculate on the “What if?” What if two satellites collided while the space shuttle was doing a repair to the Hubble Telescope?

So it wasn't so much accuracy as believability that was important.

Jonás Cuarón: We really tried to be as accurate, but obviously we're writers… So I tried to become as big of a space expert as possible but still, I don't want to claim anything because I know there'll be a scientist and a physicist that will show up and say I'm wrong.

Oh, they always do that.

Alfonso Cuarón: This is a film – at the end the film is nothing but a metaphorical journey. Yes, I wanted to honor that realism in space because I'm fascinated by it and Jonás is fascinated by it and for that journey to be more powerful, it had to be as grounded as possible. And by that, I mean grounded in today. We didn't want to create a science fiction or a fantasy comic book kind of reality.

Arguably you could do exactly the same story from a futuristic standpoint, but we wanted to keep it in the present and with the technology that exists nowadays. So we tried to be as accurate as possible but again in the frame of our fiction, so we did invent which tools, which elements, we had in space to play with.

What was the genesis of this project?

Alfonso Cuarón: Jonás had written a screenplay called Desierto – it’s in preproduction right now – and he wanted me to give some notes. I read it and said, "Well, I don't have that many notes, but I would love you help me to write something like this."

Jonás Cuarón: Desierto and Gravity, what they have in common is an obsession I had at that point with a narrative form that you know you see in movies like Duel, which Richard Matheson wrote, or Runaway Train [Screenplay by Djordje Milicevic and Paul Zindel and Edward Bunker] or even A Man Escaped by Robert Bresson where like the idea is to strip down the narrative to its basics, to its bones. I found that very challenging as a writer. How do you manage to communicate everything you want to an audience when you have such restricted elements, when you have just two characters stranded in space? It was an interesting challenge.

Alfonso, would you say working with your son helped you as a writer to weave the elements of the story together tighter?

Alfonso Cuarón: Working with my son just came with a new fresh kind of energy and took out my prejudices. You know, you start doing films and you write stuff and you get recognition and then you start shying away from the notion of entertainment. And he was like, "No, it's about having fun! You can do exactly the same thing and have fun."

Part of his theory was to do a very lean narrative with no subplots. A tiny, tiny, tiny microscopic story, just enough for audiences to feel comfortable enough that they don't start asking questions, because the whole thing is to disarm the audiences. Don't let them engage intellectually, rationally because his idea was visceral, primal, to get narrative to the bones but also dialogue to the bones.

And audiences then would connect with the story from the standpoint of the character. They would feel the personal, emotional experiences. That was the theory. We wanted to do a theme about adversities because we recognize that it's something that it doesn't just happen in space; it's something that is part of the daily life of people.

Jonás Cuarón: It was really interesting working on it with my dad because it was this constant, challenging process where you had to be very concise and stripped down. There were lots of things and themes that my dad and I wanted to express about adversities and rebirth, but since you have so little, you have to find the ways either through visual metaphors or through the action itself to represent it in a more metaphorical type of way.

So it's a very sparse script?

Alfonso Cuarón: Well, it's very detailed in terms of the action. People ask how did a studio end up saying yes to a movie that just has one character floating in space. The truth of the matter is that, for lack of a better word, it was a page-turner. It was a tense read so the screenplay already was reflecting what the film was going to be.

Do you think that using so few characters also helped the audience invest in the emotional experience?

Alfonso Cuarón: I'm not saying that that's a universal rule, but that's what we were trying to experiment with this film. People are really getting a deep emotional involvement with the film, but if you think about it, there's very little textual information in terms of dialogue or exposition of backstories or other conventional ways for a deeper understanding of your characters.

Jonás Cuarón: It helps the investment but it also makes it a little bit challenging because when you have one character, it’s a gamble. Your idea is that the audience will invest all of this emotional ride on that character. The problem is then you have to be very careful with how you draft that character. You need to really create a connection with the audience. The same with the dialogue. You have a movie that has so little room for dialogue because it's a character lost, alone. The little dialogue that you have you needs to be very careful and very concise and to choose the right words.

When you were writing the script were you ever inhibited by what might and might not be filmable?

Jonás Cuarón: No. I'm grateful for our naïveté, particularly with my dad as producer and director, because when we sat down to write this project, at no point did we think about those things. We were sitting in front of the blank page – in front of the computer, to be exact – and just imagining the movie we would like to see. At no point did we repress ourselves – although when my dad put on the director's hat later, maybe he regretted that. But the writing process was great because we just imagined what we thought would be best for the story. Even if it then turned out to be a logistical nightmare.

Alfonso Cuarón: When I'm writing it's bliss because there is no director or producer around. I happen to also be the director and I happen to be the producer, but at that point I'm not even thinking about that. I cannot imagine how the process would it be with second-guessing and stuff.

How do you do that?

Alfonso Cuarón: That's the thing, the blissful thing of just thinking of a movie, not how you're going to do the film. That business goes later on to guys that later on they have to put together what you created. Unfortunately that guy happened to be me, and it took me another four and a half years to do the thing. While the screenplay we wrote it very quickly.

How did Ryan Stone come to be? When did you know that she was the woman for the job?

Alfonso Cuarón: We talked about themes and we had this image of this astronaut just rolling into the void. Basically from that it was very obvious to start seeing a lot of metaphors, as the character was drifting into the void getting further away from human interaction and connection and communication. This was a character that was a victim of her own inertia, a character that lives in her own bubble. So we had those things, and the funny thing is that when we started writing, it was immediate. I don't even remember if there was a conversation about that.

Jonás Cuarón: She was always “The Woman.” In the first draft she was “The Woman” because it was a character that had basically lost all life, had lost all desire of living and through this journey would have almost a rebirth. It was very important to have a female presence, a presence of fertility, not in the sexual sense but on the life-giving sense. So we always knew it was a woman, then later, when we had to choose a name, I just always liked Ryan because it's an androgynous name.

Alfonso Cuarón: We didn't want some kind of marine who’s always in that situation and had all this marine training to sort out things. We wanted Ryan to represent ordinary people. She is an ordinary person going into this big adversity in space – but slowly you learn that she had bigger adversities in life. The journey was of a character who has been very shut off from everything, and it's a journey of expansion, inner expansion. So that was pretty much the set up of how we started discussing about Ryan. Obviously the name “Stone” was about weight, a stone that is drifting in weightlessness.

Did you find that in the process you guys were contradicting each other a lot?

Alfonso Cuarón: People ask about the relationship working with my son. It's like when we're working we're just two writers working together. I always admire his writing, his narrative impulses. It's been my experience that in collaboration between writers there's always one that is wise and another one that is stubborn. And yes of course he's the wise one.

Jonás, do you consider yourself the wise one?

Jonás Cuarón: I'm definitely not the stubborn one! I guess what makes me wise is that I try to reason with his stubbornness and I have to be very grateful because he could have pulled the patriarchal card at many points or even the experience card, that “I've been writing for 20 more years than you” card. But he always allowed for that discourse. Even if he's really stubborn, he always heard me. He wants to pretend to be stubborn, but he's stubborn with open ears.

© 2013 Writers Guild of America West