The Power of Now

Can The Spectacular Now bring back the kind of classic, relatable high school movies that John Hughes and Cameron Crowe wrote in the 80s? Scott Neustadter & Michael Weber hope so.

Scott Neustadter

Scott Neustadter

Michael H. Weber

Michael H. Weber

The mistake a lot of writers make is the assumption that people cannot wait to read their stuff. You finish it, hit send and you're like, Oh my God, I just made someone's day!

—Scott NeustadterThe writing collaboration between Scott Neustadter and Michael Weber began, like so many friendships of all kinds, over a shared love of movies. Neustadter was a development executive at Tribeca Productions when Weber arrived as a college intern. Over lunch on the roof they would talk of their shared heroes (Woody Allen and Cameron Crowe), and of the scripts they were reading. They had been writing on their own but decided to take a crack at a script together. The reactions were positive enough that they kept going, and had their first success with (500) Days of Summer in 2009.

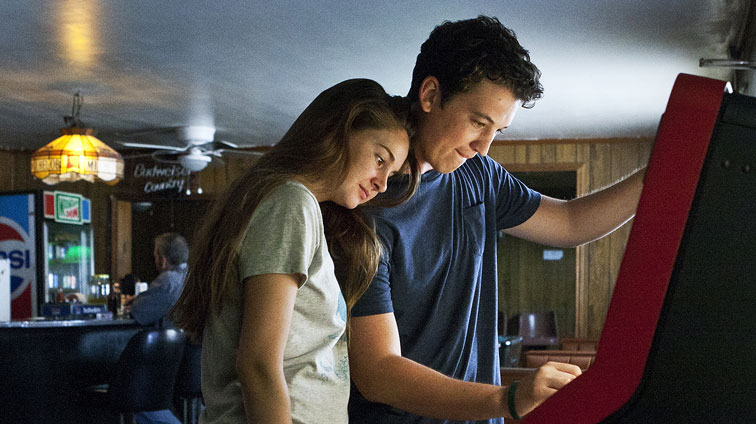

Their new film, The Spectacular Now, adapts Tim Tharp's novel about Oklahoma high schoolers, focusing on the love story between Sutter Keely (Miles Teller), a gregarious and popular, alcoholic senior, and Aimee Finicky (Shailene Woodley), a quiet girl he dates and falls in love with on the rebound from a breakup. Sutter avoids dealing with his future and starts to infect Aimee's outlook, but Neustadter and Weber work hard to avoid the clich s, handling the teenage sex, drinking and family drama with kid gloves.

The script was written as they've collaborated on all their scripts, with geographical distance between them. At first they worked over the phone and email from New York's Upper West Side to Lower East Side, then New York to England and finally New York to Los Angeles. "We get ourselves an outline, then divide and conquer trading scenes," describes Neustadter. "I'll take the first three, you take the next three, then switch. It's an impossibility for us to get anything done when we are in the same room, which becomes friend time. The further we are from each other, the better the stuff seems to be."

How fantastic a training ground for screenwriting is working in development?

Scott Neustadter: For me it was invaluable. When I was an intern I quickly discovered that executives would prefer to do lots of things before reading, and it was my favorite thing to do. When I moved to L.A. and wanted to make a real go of this writing thing, I still did coverage for seven or eight different places, while we were selling stuff. It was helpful to know what's out there and what people are interested in or not interested in. And Weber is always inspired when he reads good stuff, but I'm inspired by reading the worst stuff in the world. I'm so enamored with good writers that the amazing things I read put me in a funk. But having worked in development gave us an advantage in meetings with executives because I knew the thought process behind what they were saying. The mistake a lot of writers make is the assumption that people cannot wait to read their stuff. You finish it, hit send and you're like, Oh my God, I just made someone's day! But they have 15 of those, and they would rather do pretty much anything else. You have to remember that this is somebody's job. They love movies, and they love good scripts, but for the most part they're not working on good scripts. They're working on scripts that need a lot of work. So, when you give them something, it's helpful for us to remember to hook them in the first couple of pages, or they're going to put it down. That was always something we kept in our minds: who our first readers were.

Do you have any executive translations you can give?

Michael Weber: If they say it's good, then it's terrible. If they say it's great, then you're going to be rewriting. You just have to adjust downwards, but they're always telling you it's great. My favorite is, "We really think this is a movie, somewhere here."

Scott Neustadter: They have to start with something positive, but the lamer that first positive thing is, the more in trouble you're in.

Tell me about Spectacular Now. Did it adapt naturally from the book or was there a great deal of work involved to make it cinematic?

Scott Neustadter: It's a fantastic book with great characters, amazing dialogue and well plotted, but it was a first-person narrative told from the perspective of this character, Sutter. You realize midway through that he's not entirely reliable. He might not see himself in the same way other people see him. The question for us was, How do we do that in an interesting fashion, that doesn't tip our hand? That was one of the things we were so excited by in attacking this; how to make that cinematic?

Michael Weber: We added this framework of Sutter's college essay. It wasn't in the book but we viewed it as a fun way to get into the character's head right from the start, learn a little bit about him and understand his worldview.

Scott Neustadter: What we didn't want to do is have a voiceover heavy script throughout. So we developed the bookends, tipping you off that we are in his head as the story is unfolding, then left it be. We also had to make a conscious choice to never judge the behavior of anybody in the story. Sutter is not always up to the best stuff in the script, but he's telling you the story and you're in his head, so he doesn't really see it that way. For us, we had to not pass judgment. We have to have him behind the wheel, drinking from the big gulp without commenting on it. It's not an afterschool special.

Tell me about approaching Sutter's alcoholism. It felt more real to me than we usually see teenage drinking portrayed.

Michael Weber: It was the same approach we took with sex, with language, with all the elements that made this a real movie about teenagers. We wanted to be honest about it, not to sugarcoat it or hide from it. Like anything, it's a balancing act as we go through it. It's not the heightened tone of American Pie. Were not glorifying teenage drinking but were not condemning. It's a matter of fact that this is how kids are and we wanted it to feel authentic, more than anything else.

Scott Neustadter: The appealing question for us was, Can we really make an authentic teen drama nowadays, where we're not highlighting the fact that these are teenagers in so much as they're just people? As a result, there's nothing black-and-white. It's all gray area. Alcohol is not a horrible thing. Abuse of alcohol can definitely be a horrible thing. There's so much that we could have said good or bad about these things, but the more gray area we were allowed to work with, the more realistic and accurate this becomes as a depiction of what these kids are going through. The afterschool special version of this says that alcohol is bad, don't use it. And that's not true.

Michael Weber: At the end of the movie, there's no scene of rehab. We don't get into that. We never viewed this as a movie about drinking. It's a love story, a coming-of-age story. For us, that was the first lens through which we looked at this.

Scott Neustadter: With regard to Sutter's relationship with Aimee, we're hoping that the audience is divided about it. Toward the end of this movie, you hope that Aimee has more of a backbone than she's displaying. For us we felt, yes, you could have given her one, but this is that character, and I believe this is how she would behave in this situation. Again, it's a gray area I'm hoping this is going to work out for her but I don't know for sure. All we know is that this is probably what would really happen.

Michael Weber: And that describes all of our favorite movies, where you are walking out of the theater talking about it. Before we were working together creatively, our friendship was forged talking about movies like this that we loved. These are just the stories we like to tell.

Tell me about your involvement with post-production. You write the script but editing can be very much a part of the writing process.

Michael Weber: I loved being involved. This was the first movie we were producers on. There were a handful of producers with various instincts and backgrounds. Having lived with the script for so many years, we had a valuable point of view, but it was interesting to be in the push and pull between commercial instincts, independent instincts, the movie we would want to go see. All of that was exciting to be a part of. I'd love to do it again. Understanding how everyone else does their job makes us better writers.

The high school coming-of-age story is well trod territory. What was the greatest surprise for you, making this movie?

Michael Weber: We went to Oklahoma City to location scout, because the book is set there and we wanted to get a sense of does this movie have to be made in Oklahoma City and surrounding area, or does their high school and teenage life feel like everywhere else? And it did. But one of the more interesting things that happened was in Enid, Oklahoma, in a high school library. I turned to the student librarian, she was 16, and out of curiosity said, "What's your favorite movie about teenagers?" She thought about it for a beat and said, "Harry Potter." That was a really special moment for all of us because it validated why we were making this. We're a little older and my favorite movies were Ferris Bueller, Say Anything, and Fast Times. And they stopped making those kinds of movies about kids for a long time. We didn't want to make a movie with superpowers or vampires or boy wizards. And we didn't want to do the heightened hijinks. Nobody has sex with a pie in our movie. And those movies are great, by the way. But the movies I grew up with, that I related to the most, were a little more down the middle and relatable, and it didn't need a certain kind of metaphor.

Scott Neustadter: They used to make these movies in two ways: the relatable ones and the escapist ones. For whatever reason, they don't think there's an audience anymore for the relatable ones. They've all but ceased to exist. But those were the ones that really stuck with us. So it was our desire to see if there's a way to bring them back. The Harry Potter experience validated the fact that kids today have never seen a movie that was about their experience as regular high school kids, unless you go to Hogwarts. In which case, God bless you. I don't think anybody understands the way in which Say Anything could exist in the current cinematic marketplace. And there still might be no room for it, we don't know. We've got our fingers crossed.

© 2013 Writers Guild of America West