Today in Guild History: NLRB Okays Screenwriters to Unionize

Decided on June 4, 1938, the case established the right of screenwriters to unionize and created the framework for collective bargaining that exists today.

(6/4/2021)

A film shoots on the backlot of MGM studios in Culver City in the 1930s.

On June 11, 1937, the Screen Writers’ Guild, one of the predecessors of Writers Guilds West and East, filed 21 separate representation petitions with the National Labor Relations Board, the first step toward unionizing writers at the studios. The decision that issued a year later, MGM v. Motion Picture Producers Assn. et al. (1938), was one of the first big cases before the NLRB.

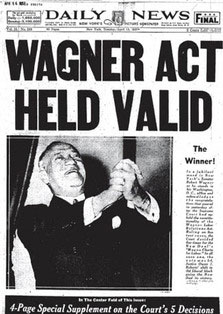

A cornerstone of FDR’s New Deal, the National Labor Relations Act was passed in 1935. Also known as the Wagner Act, the NLRA guaranteed private sector employees the right to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, and take collective action, such as strikes. Almost immediately, the Wagner Act was challenged in court and, on April 12, 1937, the Supreme Court narrowly upheld the law. A few months later, screenwriters were among the first employees at the door of the new agency seeking to exercise these rights.

MGM and the other studios resisted the screenwriters’ organizing efforts with arguments that may seem laughable today. The first argument was that screenwriters were just not the type of workers the Wagner Act was intended to cover. As the decision notes, the companies claimed that “the Act applies to the more standardized and mechanical employments,” not the creative and professional work that writers performed. A more substantial argument was that writers were independent contractors, not employees, because they didn't act like traditional employees: they didn't report to work every day, they didn't have regular hours, and they had too much control over their work. One studio groused: “some even leave Hollywood and do their work at a resort or in the country!”

But that was not what the evidence showed. In 1930s Hollywood, screenwriters had little control over their work. As the decision notes, “the producer may assign several writers to the preparation of one play at the same time. Each may work on a different part of the play. Writers may be and are taken off work to which they have been assigned, and given other work.” The Guild introduced in evidence employment contracts that gave the companies broad power to control how writers performed their duties and all rights to the resulting work. Ultimately, the NLRB sided with the writers and declared them to be employees under the Wagner Act with full rights of unionization.

One of the reasons it was possible for writers to organize on an industrywide basis was the concentration of worldwide film production in Hollywood. At the time of the MGM decision, about 70% of all motion pictures shown throughout the world were produced in the United States, and more than 90% of the motion pictures produced in the United States were produced in Los Angeles County. According to 1935 census statistics, 23,000 Americans were engaged in some facet of motion picture production, and 84.5% of those people resided in Southern California.

In retrospect, it was lucky that the MGM decision was decided when it was. The Wagner Act was new; New Deal politicians openly embraced policies favoring the expansion of collective bargaining rights. In the decades that followed, much of the progressive impetus of the NLRA has been blunted by conservative NLRB precedents, particularly as regards the issue of independent contractors.

The MGM decision was significant because it was the beginning of industrywide collective bargaining in Hollywood as we still know it. The names of the companies—at least some of them—have changed. Some companies have merged and others have gone out of business. The Screen Writers’ Guild became, in 1954, Writers Guild of America East and West. But the essential structure of industrywide negotiations remains intact. The parties have accommodated to business and technological change through the bargaining process itself rather than through legal proceedings at the NLRB or any other form of government intervention.

That original decision—to allow the Guild to organize and collectively bargain, which has never been litigated again since—has given the modern Guild an 80-year history of successful collective bargaining agreements. And it was probably the last time we had good news from the NLRB.